To Open The Sky

An historical essay on the life and work of

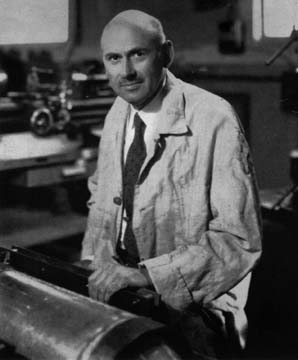

Robert Hutchings Goddard

The Father of American Rocketry

A quote from Herbert George Wells:

"There shall be no end to our striving. Man must go on, conquest beyond conquest. And when he has conquered all the deeps of space and all the ends of time, still he will be just beginning."

Part 3: Conquest Beyond Conquest

Robert Goddard's Legacy

How can we judge the work of a pioneer like Dr. Goddard, who was so far ahead of his time? I maintain that this is easy: He built rockets, and they worked. It does not matter that the science was new and strange, or that the technology was risky. The science was valid, as he proved; the technology could be made safer and more reliable, as it has been.

It has been said that extraordinary claims demand extraordinary evidence. Dr. Goddard's claims — his public speculations, if you will — were indeed extraordinary (when he first made them): He proposed to send a mechanical device into the upper reaches of Earth's atmosphere, or perhaps even beyond the atmosphere.

(Leave aside for the moment his private speculations: flying through space to other planets; ships powered by sunlight; trips to the stars, with the crews frozen so they could live long enough to complete their journeys.)

If Dr. Goddard's claims were extraordinary enough to demand extraordinary evidence, I submit that he provided that evidence. True, he did not accomplish the whole job; his rockets never launched a payload. But he achieved enough to prove to any thoughtful person that the whole job was achievable. Why, then, did his work attract so little support?

That was a trick question. For, of course, his work did attract support, or at least strong interest — just not from the right people.

- The German researchers were well aware of the value of Goddard's work. During much of the 1930s, they wrote to him requesting information of the sort that scientists usually share with each other. Goddard did not oblige them because in most cases he was not ready to publish. He was also aware of the military significance of his designs and foresaw that Germany was likely to become an enemy once again. The huge complex at Peenemünde on the Baltic Sea is a testament to how seriously The Third Reich took Goddard's concepts. After the war, Dr. Walter Dornberger (former commander of Peenemünde) wrote that he recalled the hunger in Germany for news of Goddard's work: "The reason was that Professor Goddard was one of the outstanding rocket pioneers in his country. We could not understand that a man of his genius did not get sufficient support of his government in time." [1]

- Stalin's Russia understood the importance of Goddard's work. His 1919 paper triggered in that country a rediscovery of Tsiolkovsky and other early experimenters, and set in motion the creation of the Soviet aerospace establishment which proved itself so formidable a generation later.

- Many (though not all) of Dr. Goddard's fellow scientists perceived the possibilities inherent in his experiments, and encouraged his efforts.

- Private groups in the U.S. and elsewhere fully appreciated the potential of Goddard's work, and saw where it might lead. Notable examples are the American Rocket Society and the British Interplanetary Society.

In retrospect, it seems that the U.S. Military was the only group that was NOT aware of the military significance of the rocket. Harry Guggenheim arranged for Dr. Goddard to pitch the possibility of long-range, liquid-fueled rockets (what we know today as ICBMs) to a tri-service panel in May of 1940. (This, remember, was 15 years after he began flying his rockets.) After listening closely, the Army representative said he thought the war (then raging in Europe) would be won by trench mortars. The attendees from the Navy and Air Corps were only interested in those JATO units. (Dr. G. Edward Pendray, a founder of the American Rocket Society, is said to have described the decision to put Goddard to work developing these devices as equivalent to "trying to harness Pegasus to a plow.") [2]

It is also worth noting that the governments of Britain and America, both with strong pro-rocket groups, were slower than Russia and Germany in devoting significant resources to rocket development. Deliberative democracy vs. impulsive dictatorship? Perhaps, but if so it suggests that the leaders of democracies cannot recognize worthwhile new ideas even if they work, unless those ideas happen to solve a problem that's hanging over their heads.

So perhaps the greatest legacy Robert Goddard left us is not his developments in astronautics, valuable as those are, but the reminder of how pervasive shortsighted expediency has become in this country.

Though Robert Goddard might have achieved far more had not cancer cut his life short in 1945, a fair assessment must be that what he did achieve, in the face of his own poor health, plus general ridicule, chronic shortages of funds, and government indifference, is truly monumental. Speaking from the perspective of 1960, Dr. Pendray declared: "If his own countrymen had listened to Dr. Goddard, the United States would be far ahead of its present position in the international space race. There might, in fact, have been no race." [3]

However belatedly, the truth of this observation is now officially recognized. Some of the many posthumous tributes to Goddard are:

- There is (or was) a Goddard Wing at the Roswell Museum, with the Eden Valley launch tower as an important exhibit.

- The U.S. Naval Powder Factory at Indian Head, Maryland opened a Goddard Power (not powder) Plant in June 1957.

- The United States 86th Congress in September 1959 ordered the mint to design and strike a gold medal honoring Goddard's pioneering research in rocket propulsion.

- Goddard joined a very select group in June 1960 when the Smithsonian awarded him its Langley Medal for achievements in aerodynamics.

- In Auburn, Massachusetts, a granite marker was unveiled in July 1960 at the site of the first liquid-fuel rocket flight. This marker came from the American Rocket Society. The ARS also established a Goddard Medal to be given annually for the best contribution to rocket research.

- And finally, NASA named its center closest to Washington the Goddard Space Flight Center. GSFC dedication ceremonies were held on the chilly afternoon of 16 March 1961, exactly 35 years after that first Auburn flight.

NOTES:

[1] — Lehman, pp. 389-390

[2] — Yost, p. 153

[3] — Yost, p. 144

REFERENCES

PICTURE CREDIT

Goddard in his Lab — Yost, plate 7B

| Disclaimer | Claimer |