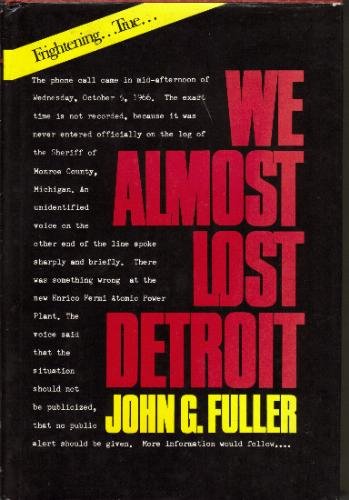

| WE ALMOST LOST DETROIT John G. Fuller Carl J. Hocevar (Fwd.) New York: Reader's Digest Press, 1975 |

Rating: 5.0 High |

|||

| ISBN-13 978-0-88349-070-9 | ||||

| ISBN-10 0-88349-070-6 | 272pp. | HC/BWI | $? | |

It was a horrible idea at the outset. Starting construction of a commercial breeder reactor with so many scientific and technical questions unanswered, and against the wishes of the Advisory Committee on Reactor Safeguards. But that is what Detroit Edison did. The impetus was provided by Walker Cisler, its president, beginning about 1951. His push for speedy development of commercial reactors was aided by the AEC, first with basic research, then with development of prototypes.1 The AEC, under Chairman Lewis Strauss (an investment banker appointed by Eisenhower in 1954), was also gung ho for commercial nukes. It helped Cisler's push to build his showpiece Fermi Atomic Energy Plant near Detroit by paying for some of the equipment. And, as John Fuller reports here, it concealed from the public and from Congress the content of studies that would have prevented passage of the Price-Anderson Act. Without this federal government cap on the liability of utility companies in the event of a reactor accident, the commercial nuclear power industry would have died a-borning — or at least been postponed for a generation while more of the technical questions were ironed out in prototypes.

Fuller describes the crucial contretemps in Chapter 3. Briefly, what happened was this: A safety analysis was required before the AEC would issue a construction permit for Fermi. Cisler's team supplied one. It did not satisfy the Advisory Committee on Reactor Safeguards. They told the AEC this in a letter, which Strauss immediately marked "administratively confidential."2 No word about whether or not the permit had issued reached the Joint Committee on Atomic Energy in Congress. Three weeks later, testifying on another matter, Strauss casually mentioned he would attend the groundbreaking for the reactor. Another AEC commissioner, Thomas E. Murray, told Congress the very next day that the safety plan for Fermi was not satisfactory, that no permit had issued, and that the breeder was the most dangerous type of reactor.

The AEC issued a construction permit on 4 August 1956, while Congress was in recess.

There followed a lengthy, trouble-plagued construction process. On page 123, Fuller lists some of the problems:

He was a founder of the Atomic Industrial Forum in 1952, and its first president. Educated at Cornell, he was intelligent, hardworking, and dedicated to bringing nuclear power on-line commercially as a replacement for fossil fuels. But with the Fermi plant, he clearly jumped the gun. During its construction, he gave no quarter to critics. When UAW president Walter Reuther filed suit against the plant, Cisler played the socialism card:

"We are headed down the road to a socialist state." – Page 51 |

He was honestly concerned about safety, however, and strove mightily to resolve any safety issues with the plant. After the partial meltdown in 1966, he displayed some humility. But he soon recovered.

With meticulous detail, Fuller describes the subsequent, eventful history of the Fermi plant. Construction was completed in early 1963, and fuel loading commenced in July. A further series of troubles ensued. The one that could not be overcome took place on 5 October 1966, when pieces of zirconium cladding broke off a protective device in the bottom of the reactor vessel.3 Carried upward by the molten sodium coolant, these blocked some of the channels through which coolant flowed over the fuel rods, causing four of the rods to overheat and spill radioactive fission products into the containment. The reactor was successfully shut down, but remained in a dangerous condition. The condition of the core was not known, and any attempt to learn that condition might induce further damage. The great fear was something the AEC had continually tried to downplay: the possibility that a small amount of damage might lead to sudden compaction of enough fuel to attain critical mass.4 In plain language, this meant an atomic bomb. Working with extreme care, the team at Fermi was able to contain their accident. After three years, they had repaired the reactor and in May 1970 were preparing to restart it. A coolant line broke, releasing 200 pounds of now radioactive sodium. Other pipes burst, adding water to the mix. Fire ensued. This too was contained, and in July they tried again, cautiously bringing power up to its rated level of 200 MW thermal. But it was too late; too much had been spent on the plant5 that had produced useful power for only 378 hours. Investors were pulling out. The Michigan Public Service Commission withdrew its approval. The AEC ordered suspension of operations on 27 August 1972.

Fuller also describes the larger battle over nuclear power plants with great thoroughness. This included Walter Reuther's lawsuit, eventually overturned by the Supreme Court in a 7:2 decision. It included the several studies of reactor safety: WASH-740 (1955); the independent Gomberg Report6 (1957); the suppressed update to WASH-740 (1964); the watered-down version of it called WASH-1250 (1973); and the Rasmussen Report7 (1975). Fuller describes the last two reports as deceptively reassuring. To put it mildly, the AEC does not shine in his account. Strauss's hiding of the letter from his advisory committee was no aberration, but part of a pattern of suppressing or watering down reports that would cast doubt on the commercial viability of fission power.

"In more than seven years of working with the AEC's safety research program for light-water reactors, I had an excellent opportunity not only to become familiar with the AEC's research programs and safety analysis methods, but also to observe the basic underlying philosophy of the AEC. This attitude was primarily one of trying to prove that existing reactors were safe rather than independently assessing the adequacy of the safety systems. While many of the scientists working on the safety research were conscientious and tried to point out valid problems regarding reactor safety, their questions were largely ignored." "The AEC, as a government agency, had an obligation to serve the public in an unbiased manner. It did not. The new Nuclear Regulatory Commission has been formed specifically to regulate, and not promote, the nuclear industry. But after the first several months of operation, there does not appear to be a truly unbiased view prevalent in the NRC." – Carl Hocevar, Pages viii-ix |

Fuller remarks in at least two places how this pattern, and the resultant spending of enormous sums on building plants, drew funds away from other potential means of reducing our dependence on fossil fuels: not only solar and geothermal, but thermonuclear fusion.8

In this account, John G. Fuller (1913-1977) has produced what is almost certainly his best work. It's based on indefatigable research; he apparently sat though all the AEC hearings during the time he was writing the book, as well as a number of other meetings. And of course he read widely on the subject. The result is a very readable life history of a reactor. A number of photographs augment the text. A bibliography lists 195 entries. The endnotes are thorough, the index is complete. There are a number of factual errors which, taken together, show that Fuller had a poor understanding of science — which led him sometimes to overstate the dangers of exposure to radiation. But because of the quality of work he put into this book, and because his assessment of the cavalier nature of reactor development during those years is correct, I can overlook the mistakes and give him full marks.

To contact Chris Winter, send email to this address.

To contact Chris Winter, send email to this address.