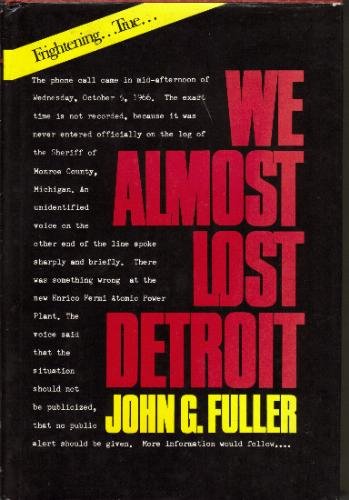

| WE ALMOST LOST DETROIT John G. Fuller Carl J. Hocevar (Fwd.) New York: Reader's Digest Press, 1975 |

Rating: 5.0 High |

|||

| ISBN-13 978-0-88349-070-9 | ||||

| ISBN-10 0-88349-070-6 | 272pp. | HC/BWI | $? | |

| Page 8: | "As a new, man-made element, plutonium was not only the source of the explosion of the nuclear bomb, but was also perhaps the most deadly poison in the world." |

| Fuller does qualify this statement with "perhaps", but that does not excuse his overblown claim. There are many substances more deadly, pound for pound, than plutonium. Also, he misses the fact that uranium was used in a nuclear bomb. |

| Page 12: | "Chalk River easily met the requirements and the NRX experimental reactor was built on December 12, 1952." |

| All in just one day? No, in fact it was built more than six years before this date, which is the date of its accident. See page 14. |

| Pages 12-13: | "So safe, in fact, was the design of the NRX, that it had some nine hundred devices for shutting it down in an emergency and only one for starting it up." |

| Nine hundred devices to go wrong. This is not the way to enhance safety. |

| Page 13: | "The splitting not only gives off an enormous amount of heat, but sends two and a half more neutrons out of an atom's nucleus to repeat the process." |

| This indicates misunderstanding of the statistical nature of neutron production in fission. |

| Page 21: | "The breeder reactor had special problems. Besides producing plutonium, its core could turn into a critical mass. It also was cooled by liquid sodium, a thick viscous fluid that is subject to special risks. In contact with water or air, the sodium could explode and flash into fire. In case of disaster, events would occur one thousand times faster that with the light-water reactor." |

| No one knowledgeable says a reactor can explode like a nuclear bomb. But that is what Fuller's claim of critical mass implies. He's wrong. I also doubt his claim of a factor-of-1,000 speed increase. |

| Page 22: | "When nuclear fuel, usually uranium, melts like a candle into a waxy, drippy mass, it can become unpredictable. [...] If it forms into a thick mass, it is possible for it to cause either a chemical or a small nuclear explosion that might breach the containment building." |

| Again the erroneous claim that a reactor can explode like a nuclear bomb. |

| Page 23: | "If a runaway meltdown should develop, and the fuel should reassemble itself at the bottom of the reactor, it was entirely possible for a breeder reactor like EBR1, or the breeder planned for Michigan, to turn itself into a mass similar to that of a nuclear bomb, not with the same explosive power, but still a significant contamination potential if the containment were breached." |

| I think the portion that jumps out at anybody who reads this is "similar to [that of] a nuclear bomb." Fuller may understand the distinction, but he's conveying it poorly. I'm not sure this isn't intentional. |

| Page 23: | "If it were compact, Zinn felt, it could 'disassemble the machine.' In plain language, this meant a nuclear explosion." |

| Perhaps — but perhaps not. |

| Page 25: | "As the most toxic substance known to man, it has been estimated that 1/30,000,000th of an ounce of plutonium could bring on cancer if inhaled." |

| Read my lips: Not most toxic! And stop dangling your participles. |

| Page 39: | "Further, if the incredible should happen, there must be no way that the tightly sealed containment building could be breached by an explosion or a dreaded sodium-air reaction that could eat up all the oxygen and collapse the building." |

| If the containment dome is proof against the overpressure of an explosion, it's not likely to be overstressed by the 15psi difference between sea-level atmosphere and vacuum. Furthermore, "eating up all the oxygen" would cause just one-fifth of that pressure difference, because air is only 21 percent oxygen. In any case, a valve that would relieve negative pressures and seal against positive pressures is no big deal. |

| Page 39: | "Every conceivable type of accident was spelled out in detail, and the ways of controlling it assessed. One possibility concerned a surge of reactivity of the chain reaction during the operation or during the loading of the fuel. Another was the fast reassembly of the material in the core during a meltdown when the uncontrolled fuel would pile up dangerously. Either could lead to a nuclear runaway or explosion." |

| Read my lips: No nuke praxis. |

| Page 44: | "Special studies on the outside limits of danger from a nuclear power plant were already underway." |

| Missing space: S/B "under way". |

| Page 51: | "He also reminded the public that during a recent congressional hearing, Strauss had called the fast breeder the most dangerous of all reactors." |

| No: it was Thomas E. Murray who made that statement. |

| Page 58: | "Even though an exuberant AEC public information man once tried to soften the ugly potential of fallout by defining the radioactive poisons as "sunshine units", any fission product inhaled or absorbed by the skin is deadly." |

| No: overblown claims on both sides. (Was this the origin of the name "Moon Unit Zappa"?) |

| Page 58: | "Among the most deadly of the fission products are Cesium-137, Strontium-90, Iodine-131, and Plutonium-239." |

| It's a stretch to call plutonium a fission product, since it does not result from the breakup of uranium atoms. |

| Page 67: | "One problem in the use of boron rods was that they tended to capture many neutrons that could be used to leak into the raw uranium blanket and produce plutonium, and thus created less new plutonium fuel. For this reason, the rods rested high above the core when the reactor was running, so that they wouldn't absorb too many of the neutrons." |

| No; the rods are "high above the core" to allow the reactor to run. Boron or cadmium, control rods are there to do one thing: control the rate of fission, and stop it when necessary. But there may be valid technical reasons to prefer boron in a breeder, which Fuller doesn't convey clearly. |

| Page 67: | "In fact, constant public relations statements were issued by the AEC that. a reactor simply couldn't explode like an atomic bomb. How these statements could be made in direct contradiction to so many sober and reliable studies by qualified scientists remained a puzzle." |

| Probably the answer is that the technical details of meltdowns in operating reactor designs preclude it. |

| Page 77: | "The worried officials at Windscale watched the barometer—the wind direction indicator—and the temperature with considerable concern." |

| I think this is supposed to describe three weather instruments. Certainly Fuller knows a barometer does not indicate wind direction. |

| Page 90: | "Any container or cask used for moving an irradiated fuel rod around must always be kept filed with a liquid coolant. The coolant's loss means inevitable disaster, since no steel container can hold back radiation without it. The rays have no respect for mere metal." |

| Another technical misstatement. Steel can hold back radiation just fine, given that it's thick enough for the radiation levels expected. What it can't do is hold back freshly removed fuel rods that are not cooled, since they will quickly reach temperatures beyond steel's melting point. |

| Page 97: | "Another trailer truck carrying uranium gas also overturned in Bardstown, Kentucky, with some escape of gas." |

| The word "also" is not needed. Its presence implies the same truck had previously overturned in Hanford. (The gas was probably uranium hexafluoride — UF6.) |

| Page 121: | In list of prominent protesters: "Dr. Paul Erlich." |

| Spelling: S/B "Ehrlich". |

| Page 125: | The health department also asked the AEC to make sure that [...] no leakage or radioactive materials be allowed to get out of hand." |

| I think this S/B "no leakage of radioactive materials". |

| Page 133: | Scientists varied in their views of the exact lethal doses, but 450 to 500 rads were generally considered enough to kill half the people exposed to it." |

| Number: S/B "a 450- to 500-rad dose was". (Or, just drop the last two words of the sentence.) |

| Page 134: | [Radiation's] end result, always and without fail, was the ionizing of the atoms in the body, a process the body atoms were never built for. If a molecule in the body is hit directly, it becomes a biological cripple, and worthless. Other irradiated molecules can enter the body indirectly and seek out the DNA—the blueprint or computer that tells the cells what to do—with the same results." |

| Even ignoring his confusion of atoms and molecules, this reveals a profound misunderstanding of molecular biology on Mr. Fuller's part. |

| Page 162: | Marlin Remley, an industry representative from Atomics International pointed out that if the figures showed one chance in 500 reactor years for a catastrophe, and this were true, then the risk simply would not be acceptable." |

| Missing comma: S/B "an industry representative from Atomics International, pointed out". |

| Page 162: | "...the detailed effort underway at Brookhaven." |

| Missing space: S/B "under way". |

| Page 182: | "The step-up operation would inch with meticulous care and caution toward the first goal of 200,000 kilowatts of thermal power." |

| I believe this is the first mention that the reactor output ratings are thermal versus electrical power. |

| Page 188: | "The silent splitting of quadrillions of neutrons would increase rapidly in three seconds. Then they would spit even faster as the melting increased." |

| Obviously, Fuller knows neutrons don't split. Yet I can't figure out which part of the sentence is wrong. Should it be "silent splitting of quadrillions of nuclei"? In that case the highlighted word S/B "split". But then, he might have meant "silent spitting of neutrons". |

| Page 188: | "P. M. Murphy, a General Electric nuclear executive was to say a few years later: 'It is, in our view, unlikely that one will be able to design for the worst accident permitted by the laws of nature, and end up with an economically interesting system, even after additional research and development has been carried out.'" |

| Missing comma: S/B "a General Electric nuclear executive, was to say a few years later". Also: "research and development have been". |

| Page 190: | AEC statement: "There have accumulated more than 780-reactor years without a single radiation fatality or serious radiation exposure.." |

| This is an out-and-out lie. (Nit: the figure is mis-hyphenated: S/B "780 reactor-years".) |

| Page 216: | "In other words, the actual accident 200,000 kilowatts of thermal power in eight carefully plotted steps..." |

| I believe this is the first time Fuller makes it clear that the power ratings he reports are thermal, rather than electrical, output. |

| Page 236: | "Any layman who cares to study these facts—and there are a jungle of them—can learn enough to make his own judgment." |

| Number: S/B "there is". |

To contact Chris Winter, send email to this address.

To contact Chris Winter, send email to this address.