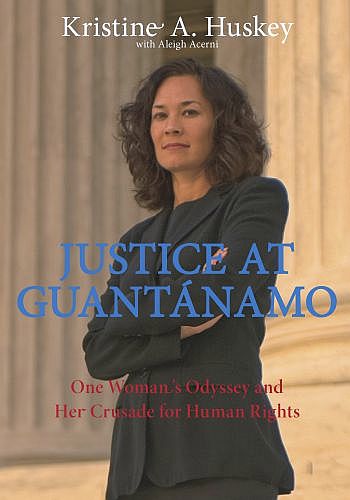

| JUSTICE AT GUANTÁNAMO Kristine A. Huskey with Aleigh Acerni Guilford, CT: The Lyons Press, June 2009 |

Rating: 5.0 High |

|||

| ISBN-13 978-1-59921-468-9 | ||||

| ISBN-10 1-59921-468-7 | 285pp. | HC | $24.95 | |

You might think this refers to the judgment of some court; it is the normal meaning of the word. The author of this book, and her colleagues, would have thought the same going in. However, I mean it to describe a verdict made without reference to any legally constituted court, or indeed to any creditable interpretation of law at all.

But I'm getting ahead of myself. Let me give you the background. The episode began with a request to Tom Wilner, a senior partner at the Washington, DC office of Shearman & Sterling, from some Kuwaiti families in mid-2002. Male members of these families had entered Iraq and Pakistan to take part in relief efforts. They regularly communicated with their families — until the U.S. invaded Iraq in October 2001. After that, it was as if their missing sons and brothers had been abducted by aliens.1

"The families have asked us to determine whether their sons are in U.S. custody," he said. "They want us to help confirm their whereabouts, find out under whose or what jurisdiction, department, or agency they are being held. If it's the U.S., the families will take it from there—but they need some help to get either a confirmation or a 'no' from our government." – Page 142 |

Nine prominent law firms in the Washington, DC area had turned the families down, deeming their request "too controversial." Given the atmosphere of those days, vibrating with the echoes of al Qaeda's attack on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, it is an understandable position. Fortunately, Shearman & Sterling took another position.2 Tom Wilner explained it on page 154: "We're going to have to sue the bastards," Tom said. "That's the only way to force them [the U.S. government] to be accountable."3

So began a six-year effort by Tom Wilner, Kristine Huskey, and Neil Koslowe to obtain justice for their twelve clients — not to free them, but merely to force the government to grant them a fair trial. Remember that these Kuwaitis, citizens of a U.S. ally, were being held without charges. After two and one half years of reversals, they were supported by the Supreme Court, which held that the detainees did have the right under U.S. law to challenge their detention.

"The Supreme Court's decision came out on June 29, 2004: The opinion reversed the earlier rulings, and held that federal courts did have the jurisdiction to hear the habeas petitions of prisoners at Guantánamo after all, according to a federal statute dictating that if you are in the custody of the United States, you can challenge your detention—regardless of where you are being held or who you are. Finally, after two and a half years of continuous litigation, we were starting to get somewhere. Our clients were going to have the opportunity to try and prove their innocence. And, we would get to meet them for the first time." – Pages 172-3 |

Now that I've done additional research on one of the Kuwaitis mentioned in this book, I find that the story is not so clear-cut as Ms. Huskey's account implies. He is the man she calls Fawzi, identified in most accounts as Fouzi Khalid Abdullah al Awda. Evidence recently disclosed by the U.S. indicates that his passport was found in an al Qaeda safe house, and that he reportedly admitted attending one of their training camps for a day.

Fawzi was released to Kuwait on 5 November 2014 on the condition he will be on probation there for one year. It does appear that some justification for holding him so long exists.

My admiration of Kristine Huskey has not lessened. She was dedicated to the cause of human rights, and clearly still is dedicated to that cause. She worked her tail off for her clients. Since she had no way to learn of this evidence by the time her book went to press, I cannot fault her assessment of her client Fawzi. And, like all detainees at Gitmo, he was mistreated.4

The administration responded by creating Combatant Status Review Tribunals. Neil Koslow quite aptly called these CSRTs "kangaroo courts." The author summarizes their defects (features, not bugs, for the government) thus:

"The CSRT procedures, in fact, did not look anything like our own criminal justice system, or even any of the military hearings held in past wars. With a CSRT, the detainee was not allowed to have a lawyer; secret evidence could be used against him; evidence obtained by torture could be used against him; and the executive branch (the president or DOD), not some impartial court or tribunal, had the final say." – Page 176 |

Being based on case law, the 2004 victory could be shot down by legislation. And it was shot down — by the Detainee Treatment Act, which passed on 30 Dec 2005. The DTA negated the Supreme Court ruling that allowed legal representation to Guantanánamo prisoners based on the habeas corpus law.

The next round in this bout was Hamdan v. Rumsfeld (2006), in which the Supreme Court held the CSRTs unconstitutional because they were procedurally one-sided and did not provide the protections guaranteed by the Geneva Conventions. The administration's riposte was the Military Commissions Act of 2006.

Only one possible remedy was left: the Constitution. In June 2008, ruling in Boumediene v. Bush, the Supreme Court held that the Constitution did guarantee prisoners a habeas corpus right to challenge their detention. This could not be set aside by Congress; but the 68-page ruling left it up to lower courts to set the rules under which challenges could be conducted. The logistics get complicated at this point. Suffice it to say that the government chose to stall. In August 2008, according to the author, they were still claiming they needed more time to make the case for holding any prisoner. At this time, four of the Kuwaitis were still being held.

The last of them was allowed to return home only at the end of 2014.

To contact Chris Winter, send email to this address.

To contact Chris Winter, send email to this address.