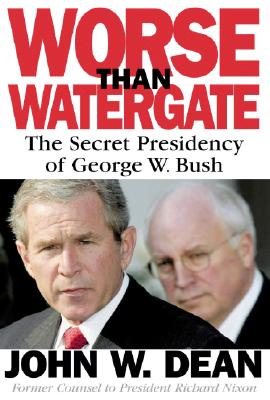

| WORSE THAN WATERGATE The Secret Presidency of George W. Bush John Dean New York: Little, Brown & Co., 2004 |

Rating: 4.0 High |

|||

| ISBN-13 978-0-316-00023-9 | ||||

| ISBN 0-316-00023-X | 253pp. | HC | $22.95 | |

John Dean is part of American history. As White House counsel to Richard Milhouse Nixon (1913-1994), he participated in the Watergate coverup. This notorious episode began on 17 June 1972 when a team of political operatives known as the "plumbers" broke into Democratic National Headquarters at the Watergate Hotel. The break-in, masterminded by FBI agent G. Gordon Liddy, was supposed to look like a simple burglary. Its real purpose was to plant a listening device and steal political strategy documents that could be used by the Committee to Re-elect the President (later known as "CREEP".) The plumbers were caught in the act. Nixon tried to cover up his involvement. He failed. John Dean was among those indicted; he was convicted of obstruction of justice and served 127 days in prison.1 When the full extent of the political operation was revealed, Nixon resigned under threat of impeachment. John Dean wrote the books Blind Ambition and Lost Honor about his career, with a focus on Watergate. The scandal will stand forever as a symbol of the abuse of presidential power — and as a time when the Constitution's balance of powers proved its worth.

In his most recent book, Dean compares George W. Bush to Nixon, previously the most secretive president.2 This is both good and bad for "Dubya's" reputation; Dean judges him to have more drive and somewhat higher intelligence than he is usually accorded; but his administration comes off as even more secretive and manipulative than that of "Tricky Dick".

Dean points out that this secrecy extends into many areas normally deemed to require public exposure: personal character, state of health, financial position, business relationships. He documents Bush's sweet deal with the Texas Rangers baseball team and the "golden parachute" Cheney received when he left Halliburton — stocks and options reportedly worth $62.6 million. Neither candidate said much about these former business dealings during the 2000 campaign, though Joe Lieberman alluded to Cheney's bountiful severance package during their debate.3 Questions about Cheney's financial dealings with the autocrat Heydar Aliyev, late dictator of Azerbaijan, are also raised. The vice president's heart condition was a concern and remains so, especially given his unprecedentedly large influence, but Dean quotes independent cardiac specialists as saying that administration comments on the subject fall short of responsible disclosure. Indeed, the whole pattern of behavior described in Chapter 2 is summed up by its title: Stonewalling. And when it comes to Halliburton, Cheney's golden parachute seems merely the tip of a mammoth financial iceberg.

One of the first acts reported in Chapter 3, "Obsessive Secrecy", is that Bush, learning in December 2000 that the Supreme Court ruled in his favor on the disputed presidential election, sealed his gubernatorial records and shipped all 60 pallets' worth to his father's presidential library. Texas has a strong public records law, and this flouted it since Bush had omitted the required consultation with the State Archivist, Peggy Rudd. Ms Rudd objected and prevailed in May 2002. But Bush apparently found a way to exploit a legal technicality and keep those papers away from the public.

Dean provides extensive evidence in the remainder of the chapter (indeed, throughout the book) that this pattern of concealment, of avoiding public accountability, is the hallmark of the Bush-Cheney administration. Such secrecy, of course, requires controlling the press. In the presidency, as is well known, Bush bars journalists who ask tough questions from press conferences. He ended the long tradition of granting the first question to Helen Thomas, doyenne of the press corps, because she called him the worst president in U.S. history. Dean relates a May 31, 2002 contretemps: Bush blasted reporter David Gregory, fluent in French, for speaking that language to Jacques Chirac at a joint press conference in Paris.

Another facet is image control. Dubya's White House relies on it, not only staging ceremonial events like the first anniversary of 9/11 (see page 73) and the "mission accomplished" fighter landing on the carrier Abraham Lincoln but going so far, according to Paul O'Neill, as scripting cabinet meetings.4 And next we come to the claimed sanctity of "executive deliberations", which Cheney invoked to shield the makeup of Bush's National Energy Policy Development Group, which Cheney chaired.5 Finally, Dean discloses an executive order issued by Bush which effectively overrules the Presidential Records Act of 1978, enabling an incumbent president to seal not only his own records but those of a former president, should the former president or his designated representative request it.

Also abundantly documented elsewhere is the Bush-Cheney pre-9/11 indifference to outside advice on the threat of terrorism. Dean reports that they downplayed the importance of the Hart-Rudman Commission, a multi-year assessment of American security begun during the Clinton administration. It put terrorism at top priority and anticipated an attack on the U.S. Among its recommendations was the formation of a Cabinet-level Department of Homeland Security. In May 2001, Bush effectively killed this by announcing an Office of National Preparedness within FEMA. Dean also mentions the low priority accorded information briefed to the Bush transition team by Sandy Berger, Clinton's national security advisor. He tells how, in the aftermath of the terrorist attacks of 9/11, Bush and Cheney resisted any investigation of how the terrorists were able to evade U.S. intelligence, and later sought to control such probes.

The book reads a lot like an extended version of a prosecutor's closing statement to the jury in a criminal case, with John Dean, J.D. the prosecutor and the American public the jury. It is a work of true scholarship, thoroughly end-noted and indexed. Yet it has the outraged tone of a polemic, and I cannot help but wonder (especially given the spate of Bush-bashing books, of which he is certainly aware) why John Dean took the trouble to write it. I doubt he has a political axe to grind, after so long; he now works out of Beverly Hills as an investment banker. I really have no grounds to suspect anything other than a sincere desire to bring his unique perspective, gained during Watergate, to bear on another impending constitutional crisis. And he is indisputably right in his general assessment of the current administration. Thus I strongly recommend it be read, and because it has information I haven't seen elsewhere I suggest it may also be a keeper. It also contains two appendices. Appendix I dissects the 8 core arguments that Bush used to justify the war with Iraq, identifies their sources, and provides on-line references for some of them. Dean labels these arguments "purported facts", and successfully debunks the majority of them. But this debunking fails for "Purported Bush Fact 2" and "Purported Bush Fact 3" because Bush's claims effectively match the source statements, and for "Purported Bush Fact 4" where Dean accuses Bush of overestimating the quantity of "munitions" by a factor of 2 (30,000 vs. 15,000) but in fact the 15,000 in the UNSCOM report refers to artillery shells, not to munitions of all types. Appendix II lists a number of watchdog organizations and their Web sites.

Worse than Watergate is well-written and informative, and has few grammatical errors. But it also has defects: occasional repetitiveness and overzealousness, plus the flawed debunking in Appendix I. I recommend it, but cannot give it my highest rating.

To contact Chris Winter, send email to this address.

To contact Chris Winter, send email to this address.