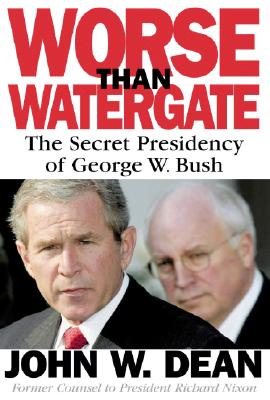

| WORSE THAN WATERGATE The Secret Presidency of George W. Bush John Dean New York: Little, Brown & Co., 2004 |

Rating: 4.0 High |

|||

| ISBN-13 978-0-316-00023-9 | ||||

| ISBN 0-316-00023-X | 253pp. | HC | $22.95 | |

Throughout the book, John Dean is extremely critical of the administration of G. W. Bush, and especially of his vice president (or co-president?) Richard Cheney. It is fair to ask what makes Dean, the Nixon White House counsel who participated in the Watergate coverup, come down so hard on another Republican administration. I think this sums it up rather well:

Secrecy — the first refuge of incompetents — must be at bare minimum in a democratic society, for a fully informed public is the basis of self-government. Those elected or appointed to positions of executive authority must recognize that government, in a democracy, cannot be wiser than the people. – House Committee on Government Operations, 1960 |

In his condemnation of the administration of George W. Bush, John Dean only lists a sampling of what he regards as that administration's mistakes. Here, I present just a sampling of Dean's list. Yet I think it will be enough to get across his motivation in writing this book. I've included external links in the text to facilitate further research.

Bush's sweet deal with the Texas Rangers baseball team and the "fortuitous" timing of his sale of Harken Energy stock are well documented. (See e.g. Shrub by Molly Ivins and Lou Dubose.) Cheney has succeeded in keeping his dealings less public. An example is the "golden parachute" Cheney received when he left Halliburton — stocks and options reportedly worth $62.6 million.1 The New York Times reported in July 2000 that Halliburton subsidiaries sold parts to Libya and Iraq while those nations were under sanction.2 Similarly, because of the actions of its late dictator Heydar Aliyev, Azerbaijan was embargoed under section 907 of the Freedom Support Act. Yet Cheney was one of Aliyev's principal backers in the U.S.3 Neither candidate said much about these former business dealings during the 2000 campaign, though Joe Lieberman alluded to Cheney's bountiful severance package during their debate.4 And when it comes to Halliburton, Cheney's golden parachute seems merely the tip of a mammoth financial iceberg.

The vice president's heart condition was a concern during the 2000 campaign.5 At 3 A.M. on the morning of 22 November 2000, during the "counting of the chads", he was taken to George Washington University Hospital complaining of chest pains. Bush released a statement claiming that Cheney had not suffered a heart attack, but he had. His surgeons had performed a precautionary angioplasty and inserted a stent. When in 2001 tests disclosed an irregular heart ryhthm, he had an ICD (a device similar to a pacemaker) implanted. Dean quotes independent cardiac specialists as saying that administration comments on the subject fall short of responsible disclosure. Yet despite repeated questions from the press, the administration continues to issue empty assurances.

The Eisenhower presidency (as those who, like me, are of a certain age will remember) was the textbook case of full disclosure of presidential health. Indeed, with its constant flow of bulletins on Ike's checkups at Walter Reed Army Hospital, it probably overdid that disclosure. But the present administration policy of pretending there is nothing seriously wrong with the vice president is irresponsible, especially given his unprecedentedly large influence.

The first act reported in Chapter 3, "Obsessive Secrecy", is that Bush, learning that the Supreme Court ruled in his favor on the disputed presidential election, sealed his gubernatorial records and shipped all 60 pallets' worth to his father's presidential library. Texas has a strong public records law, and this flouted it since Bush had omitted the required consultation with the State Archivist, Peggy Rudd. Ms Rudd objected and prevailed in May 2002. But Bush apparently found a way to exploit a legal technicality and keep those papers away from the public.

Such secrecy, of course, requires controlling the press. In the presidency, as is well known, Bush bars journalists who ask tough questions from press conferences. He ended the long tradition of granting the first question to Helen Thomas, doyenne of the press corps, because she called him the worst president in U.S. history. Even innocent initiative can bring a reprimand. Dean relates such a contretemps: On 31 May 2002 Bush blasted reporter David Gregory, fluent in French, for speaking that language to Jacques Chirac at a joint press conference in Paris.6

Another facet is image control. Dubya's White House relies on it even more than did Reagan's, not only staging ceremonial events like the first anniversary of 9/11 (see page 73) and the "mission accomplished" fighter landing on the carrier Abraham Lincoln but going so far, according to Paul O'Neill, as scripting cabinet meetings.7 And next we come to the claimed sanctity of "executive deliberations", which Cheney invoked to shield the makeup of Bush's National Energy Policy Development Group, which Cheney chaired. The bottom line here is that the GAO sued the vice president to get the information, only to have a GOP-friendly judge throw the case out of court.8 Finally, Dean discloses an executive order issued by Bush which effectively overrules the Presidential Records Act of 1978, enabling an incumbent president to seal not only his own records but those of a former president, should the former president or his designated representative request it. (Emphasis added.)

The Hart-Rudman Commission, a multi-year assessment of American security begun during the Clinton administration, put terrorism at top priority and anticipated an attack on the U.S. Among its recommendations was the formation of a Cabinet-level Department of Homeland Security. In May 2001, Bush effectively killed this by announcing an Office of National Preparedness within FEMA.

In the aftermath of the terrorist attacks of 9/11, Bush and Cheney resisted any inquiry into those events. On page 111, Dean quotes Cheney as saying that "A review of what happened on September 11 would take resources and personnel away from the effort in the war on terrorism." Political pressure forced them to yield to a congressional inquiry. They succeeded in making it a joint house-senate committee (37 contentious members cumbersome) and diverting its focus to "the roots of the terrorism problem" (read: actions during the Clinton administration.) And they saw to it that executive privilege would limit the panel's access to critical documents.9

Families of the victims of 9/11, plus their congressmen, applied more pressure, asking for a truly independent commission. Bush and Cheney objected, but gave in "after winning the power to appoint the chairman, who also has the power to block subpoenas." (page 114) Their first choice: Henry Kissinger. He lasted only a few weeks, for he refused to disclose potential conflicts of interest. Then they chose former New Jersey governor Thomas Kean, a man with no experience in national security matters. Kean in turn picked Bush insider Philip Zelikow as executive director. The 9/11 Commission was formed, but with Zelikow running the staff.

Much has been written about the neoconservatives and their overt goal of American global hegemony.

Before George W. Bush became president, there was a rash of failures of Firestone tires on Ford SUVs. Many incidents involved serious injury or death. The two companies blamed each other. Responding to the crisis, Congress passed a law requiring auto & auto-parts manufacturers to make product safety information publicly available. The Bush administration made the safety information secret. Dean notes that this, too, is responsive — in the Nixonian sense of "responsiveness": It responds to industry requests to be let off the hook.

But concealing product-safety information pales in comparison to the way George W. Bush — unlike his father's administration — has worked to gut measures protecting the environment. Environmental attorney Robert F. Kennedy Jr. notes "the Bush administration has initiated more than 200 major rollbacks of America's environmental laws." I discuss these depredations at length in other reviews and the rants associated with them. Suffice it to say here that by lowering standards, altering scientific conclusions, muzzling or firing protesters, slashing enforcement staffs and funds, and disguising industry-coddling regulations with good public relations (e.g. "Healthy Forests"), Dubya has weakened safeguards for the American environment to a degree unimaginable before he took office. And of course any attempt to investigate such activities will be stonewalled. Dean discusses several examples new to me in the pages cited.

To contact Chris Winter, send email to this address.

To contact Chris Winter, send email to this address.