|

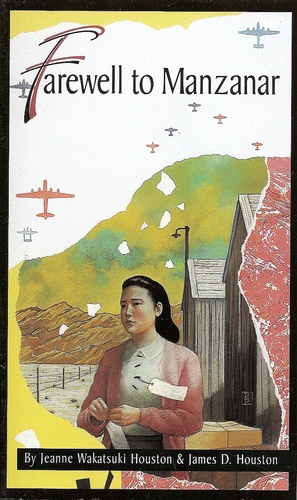

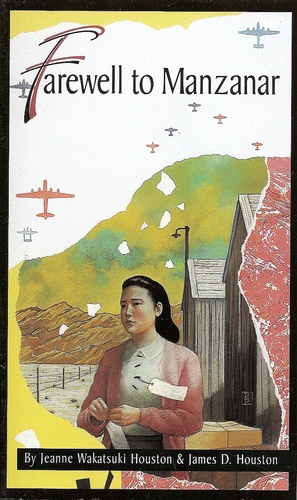

| Cover art by Pamela Patrick |

| FAREWELL TO MANZANAR A True Story of Japanese American Experience During and After the World War II Internment Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston James D. Houston New York: Dell Laurel-Leaf, 1995 |

Rating: 5.0 High |

|||

| ISBN-13 978-0-553-27258-1 | ||||

| ISBN-10 0-553-27258-6 | 203pp. | SC | $6.99 | |

On 19 February 1942, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066. This order provided for the evacuation of all residents of Japanese ancestry (most were American citizens) from the west coast of the United States and their confinement in various inland areas: concentration camps.

"It is sobering to recall that though the Japanese relocation program, carried through at such incalculable cost in misery and tragedy, was justified on the grounds that the Japanese were potentially disloyal, the record does not disclose a single case of Japanese disloyalty or sabotage during the whole war..." – Henry Steele Commager, quoted on page xvii |

Much has been written about that shameful era of U.S. history: how the Japanese lost most of their property; how none was ever convicted of acting for Imperial Japan; how the 442nd infantry regiment distinguished itself by uncommon valor; how Fred Korematsu and others lost in challenges to the internment order before the U.S. Supreme Court but ultimately were vindicated.1

This book is not like that. It is rather, a very personal account of life in one of the camps — Manzanar — and how it affected a girl who entered the camp at the age of seven.

Manzanar was the first of the ten detention camps to open. Located east of the Sierra in the dry, windy Owens Valley, it was about as remote a site as California provided at that time. The facility was primitive and physical conditions were hard to endure. But harder to bear was the distrust with its emotional impact.

"For the women in the late-night latrine Papa was an inu because he had been released from Fort Lincoln earlier than most of the Issei men, many of whom had to remain up there separated from their families throughout the war. After investigating his record, the Justice Department found no reason to detain him any longer. But the rumor was that, as an interpreter, he had access to information from fellow Isseis that he later used to buy his release." "This whispered charge, added to the shame of everything else that had happened to him, was simply more than he could bear. He did not yet have the strength to resist it. He exiled himself, like a leper, and he drank. "The night Mama and I came back from the latrine with this latest bit of gossip, he had been drinking all day. At the first mention of what we'd overheard, he flew into a rage. He began to curse her for listening to such lies, then he cursed her for leaving him alone and anted to know where she had really gone. He cursed her for coming back and disturbing him, for not bringing him his food on time, for bringing too much cabbage and not enough rice. He yelled and shook his fists and with his very threats forced her across the cluttered room until she collided with one of the steel bed frames and fell back onto a mattress. "I had crawled under another bunk and huddled, too frightened to cry. In a house I would have run to another room, but in the tight little world of our cubicle there was no escaping this scene. I knew his wrath could turn on any one of us. Kiyo was already in bed, scrunched down under the covers, hoping not to be seen. Mama began to weep, great silent tears, and Papa was now limping back and forth beside the bunk, like a caged animal, brandishing his long, polished North Dakota cane." – Page 68 |

The dust jacket calls this book "As haunting as The Diary of Anne Frank." That's hyperbolic praise; but Farewell To Manzanar is an honest and gripping tale, and shows clearly how damaging the whole episode was to its victims — and that among the victims was America's sense of honor.2 It provides a very limited part of the history, of course; but I cannot recommend this book too highly.

To contact Chris Winter, send email to this address.

To contact Chris Winter, send email to this address.