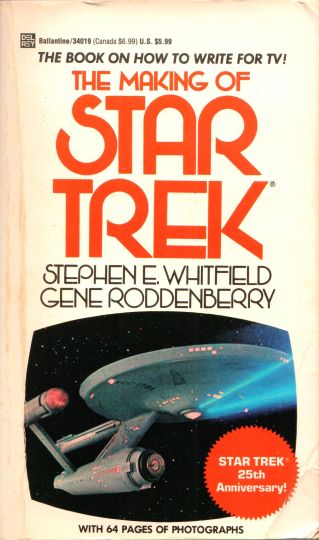

| THE MAKING OF STAR TREK Stephen E. Whitfield New York: Ballantine Books, September 1991 |

Rating: 5.0 High |

|||

| ISBN-13 978-0-345-34019-1 | ||||

| ISBN-10 0-345-34019-1 | 414pp. | SC/BWI | $5.99 | |

Why write a book like The Making of Star Trek? Simply because that show revolutionized the treatment of science fiction on television.

Previously there had been many science fiction shows on television. But, says Stephen Whitfield, they were either anthologies like Science Fiction Theater or The Outer Limits, or they were sitcoms that used the SF premise as a gimmick, like My Favorite Martian.1 Star Trek was not unique in having a continuing cast of main characters; Lost in Space had that. But, in Whitfield's telling, it was the first to treat those characters and their situations as serious, to imbue them with a credibly optimistic outlook, and to make the science as plausible as possible.

On a historical basis, Whitfield's assessment can be disputed (see the sidebar.) But he is certainly right that the American television scene during the 1960s was not favorable to serious science fiction — until Gene Roddenberry came along. Whitfield's book celebrates Roddenberry's impressive accomplishment in creating the concept of the show, and the accomplishments of the crew and cast members he assembled in bringing that concept to life. Whitfield, a former Marine like Roddenberry, had full access to the studio where the production took place, and he describes the troubles and triumphs of production in intimate detail.

The early science fiction shows that made it onto the small screen apparently came from comic strips — either directly, as with Buck Rogers and Flash Gordon, or as concepts inspired by those strips. Whatever their origin, a number of them had continuing ensemble casts.

A quick look at Wikipedia's American Science Fiction Television Series by Decade shows:

Space Patrol, according to Wikipedia, was very popular with both children and adults, and its premise of a spaceborne military force keeping order in the galaxy inevitably gets it compared to Star Trek.

It is a fascinating account that focuses on the crew — although the four major characters (Kirk, Spock, McCoy and Scotty) each get a brief chapter, and the rest of the continuing cast (Sulu, Chekov, Uhura, and Nurse Chapel) are described in another chapter. There is no doubt that the quality of the cast is a major factor in the success of the show. But Whitfield contends that the comprehensive framework Gene Roddenberry established and fought for is the bedrock on which the cast built their captivating characters. I believe he is correct. Few other series inspired such a widespread and persistent campaign to save a beloved show that had been canceled. By March 1968, NBC received 114,667 pieces of mail in support of Star Trek. This campaign succeeded in bringing the show back for a third season, although this fell short of its hoped-for five-year mission.2

It is hard to argue against the idea that the original Star Trek opened the floodgates for serious science fiction on American television. Just in its own franchise, there have been five live-action spinoffs: The Next Generation (1987-94); Deep Space Nine (1993-99); Voyager (1995-2001); Enterprise (2001-2005); Discovery (2018-); and Picard (2020-). In addition there was an animated series (1973-74) and several short episodes using Star Trek characters (2018-present). Turning to the big screen, the franchise has spawned thirteen feature films to date.3

Here I'm reviewing the Twenty-Fifth Anniversary Edition of the book, published 1991. It leaves out a few juicy details that I remember from the original: namely the embarrassment a gaffer (lighting technician) felt after shouting about Nichelle Nichols that "She's black!" (meaning poorly illuminated on the set), and what happened when a new director told William Shatner to take out his thing and call the Enterprise. Ah, the delights of the easily amused... Still, it retains the thorough description of the first-year struggles to meet deadlines while staying under budget. It does not omit the odd snafus like the repeated attempts to film green-skinned women; no matter how green the crew made the makeup, the film came back from the developer with normal flesh tones. They ultimately found out the film technician at the company they contracted was correcting the color because he thought it was a mistake.4

Perhaps most important, as he left at the end of the second season wrap party, Whitfield showed us that Star Trek had captured his soul.

It is impossible to predict at this point what will ultimately be the outcome. if STAR TREK does, in fact, come to an end next January, millions of viewers will mourn its passing. Even so, the starship launched by Roddenberry and manned by an extraordinary crew will not depart the scene without leaving some ripples in its wake. STAR TREK has proved that it really does matter to the viewer what he sees on television. Contrary to what the networks may believe, people do care about television programming. And they do not at all mind learning while being entertained. Learning implies believing. Learning also implies intelligence—the ability to see relationships, in a Vulcan, a Gorn, or a Horta. The response to STAR TREK's message is irrefutable proof of the totally inaccurate network concept of the viewer as a clod. But STAR TREK has done far more than that. It has given us a legacy—a message—man can create a future worth living for . . . a future that is full of optimism, hope, excitement, and challenge. A future that proudly proclaims man's ability to survive in peace and reach for the stars as his reward. Whither STAR TREK? It really doesn't matter. We have its legacy . . . all we have to do is use it. – Pages 401-402 |

Whitfield is vague on some details. For example, while he's usually punctilious about noting personnel changes, not until near the end of the book do we learn the sequence of script consultants on the show: John D. F. Black; Steven W. Carabatsos; D. C. Fontana; and Arthur H. Singer. The book has no index; that would have been immensely helpful. But it does have 64 pages of black & white photographs and enough anecdotes to delight the heart of any Trekkie (or do you say Trekker?) Read it and enjoy it if you get the chance, but it's not a keeper — especially at this late date.5

To contact Chris Winter, send email to this address.

To contact Chris Winter, send email to this address.