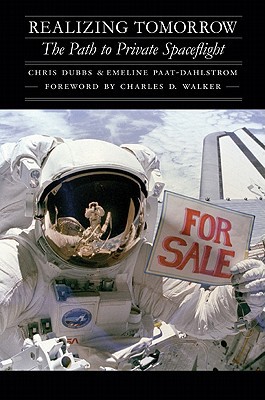

| REALIZING TOMORROW The Path to Private Spaceflight Chris Dubbs Emeline Paat-Dahlstrom Charles D. Walker (Fwd.) Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, June 2011 |

Rating: 5.0 High |

|||

| ISBN-13 978-0-8032-1610-5 | ||||

| ISBN-10 0-8032-1610-6 | 344pp. | HC/BWI | $34.95 | |

There is a hunger in the minds of men for novelty, for adventure.1 Today's Earth, crowded and largely tamed, offers little in the way of physical adventure — certainly little that's easily affordable to most of us. In recent decades, therefore, we've turned to vicarious adventuring. Of this, the space program has been among the most rewarding. We may not be taking part, but at least we can see real adventure happening.2 But how much better it would be if there was a way to fly in space ourselves!

Such dreams have existed throughout history — but, for most of it, only in the minds of a few visionaries. Not until Russian cosmonauts and our Mercury astronauts actually flew above the atmosphere did regular people accept space travel as a real possibility. Even then, it excluded all but a select few, as Tom Wolfe's The Right Stuff so vividly showed us. Yet with every successful mission, space travel came to seem that much less forbidding. The capsules accommodated two, then three astronauts. Voyages grew longer, and activities grew more complex. Skylab was launched, and astronauts repaired it on orbit. They sent back video of weightless work, and weightless antics, that forecast the possibility of ordinary people doing ordinary things in space.

All this played into the vision of space flight portrayed by Stanley Kubrick's innovative 2001: A Space Odyssey with its Pan Am shuttle carrying businessmen to a wheel space station. Pan American World Airways began taking reservations for an actual moon trip. By the time of the final Apollo mission in 1972, it had signed up 80,000 prospective members of its First Moon Flights Club.3 Pan Am went bankrupt in 1991, making those reservation cards a historical curiosity only.

Meanwhile, in the academic world, much work on moving industry into space was taking place. Princeton's Gerard O'Neill asked his summer session students whether the surface of a planet was the right place for heavy industry. They decided the answer was no, and came up with good reasons to support their conclusion. The reasons boil down to free energy from the Sun and abundant raw materials from the Moon and asteroids. Solar power could even be captured in space and beamed to Earth, replacing coal-fired power plants. But industries need workers, and workers need housing. Here the idea of "O'Neill colonies" came in. As concepts refined over several years, these were either cylindrical or doughnut-shaped habitats large enough for thousands of people. Like the station depicted in Kubrick's 1968 film, they would spin to simulate Earth-normal gravity, and would provide a shirtsleeve environment. The engineering worked out, but the logistics did not; less expensive launches on reliable heavy-lift vehicles were needed to get them started, and the funding for these never came.

But gradually the vehicles changed to impose less rigorous conditions on passengers. Apollo and its mammoth Saturn V booster gave way to the space shuttle. Flights became more frequent, with larger crews, and a greater variety of skills was needed aboard. The breakup of the Soviet Union meant its space program was strapped for cash, and it started accepting paying customers: so-called "space tourists."4 When Mir was lost as a destination, Dennis Tito (who already had a paid contract) was flown to the International Space Station — to the displeasure of NASA and the other partners except Russia. (This fascinating episode takes up a major portion of the book.) But NASA soon came around. To date, seven non-professionals have traveled to ISS. The others are Mark Shuttleworth, Greg Olsen, Anousheh Ansari, Charles Simonyi, Richard Garriott (the son of shuttle astronaut Owen Garriott), and Guy Laliberté

These people were still exceptional: exceptionally wealthy. Dennis Tito reportedly paid the Russians $20 million for his flight; the amounts the others paid are not public information, but rumors suggest higher prices. The ride might be evolving toward "E Ticket" status, but the price was still way beyond what ordinary people could afford. And governments were still the gatekeepers. There was little chance they would lower the fare price to a level anyone but millionaires could afford. NASA certainly would not — assuming they allowed paying passengers at all.

"Things there are massively overinflated," [Eric] Anderson concluded. "I'd see a million-dollar study produce a 100-page report that I could have written in college. The government has no incentive to make things cheaper. The bigger the budget, the more power they wield." – Page 125 |

And the private sector was stymied by the lack of the massive investments needed. Yet whenever a travel company looked like it seriously intended to provide the ride for a halfway reasonable price, people signed up in droves. An example is Project Space Voyage, organized by Society Expeditions, Inc. In the early 1980s it began taking deposits for trips to space and within a year had five hundred in an escrow account. (The deposits were $5,000 toward a $50,000 fare.) It was followed by a succession of private companies that tried to tap into this "go-fever" and make a little money doing so. Unfortunately, all these companies were unable to come through, for complex reasons. In general they were unable to line up sufficient investment to fund the vehicle development.

Americans have been enthused about space travel since the days of the Mercury astronauts. A long chain of companies followed, with equal lack of success. But then Peter Diamandis pulled together the Ansari X Prize, Burt Rutan won it with his SpaceShipOne, and Richard Branson contracted with Rutan to build a successor that would carry 3,000 passengers into space each year.

"In the coming months, the world gained an inkling of how Sir Richard would tackle the challenge of commercializing space. He would leave the tricky business of actually getting to space to Rutan. By 4 October [2004] Rutan had won the X PRIZE and had a second-generation, passenger-carrying spaceship on the drawing boards. Branson's flair would initially focus on the marketing. "In the fall of that year, Branson was also knee-deep in the launch of yet another project, a TV program in which he would star called Rebel Billionaire, scheduled to premiere on 9 November. It was modeled on the NBC reality program The Apprentice, starring another larger-than-life businessman, Donald Trump. The show would introduce the rogue Branson to the American public as something of an anti-Trump. Branson was an advocate for fun in the workplace, not intimidation. Eager Virgin interns on the show would not be sitting behind a desk creating spreadsheets, á la TA, but skydiving or engaging in other adventurous challenges, just like their adventure-seeking mentor. Branson had earned his success not by following the stodgy rules of business but by breaking them." – Page 219 |

Branson has earned his adventurer's plaudits, too — sailing a catamaran across the Atlantic, having to ditch, but coming back next year to set a speed record for the crossing. Turning to hot-air balloons, he made two attempts at circumnavigating the world, crashing at sea both times. Bertrand Piccard and Brian Jones in the Breitling Orbiter put an end to this quest by winning the trophy.

He thus has the credibility and the attitude as well as the business acumen and the resources to make his spaceflight venture successful.

The situation began to change when Peter Diamandis got the X Prize on solid financial footing in 2000. 18 (?) companies that had been working on suborbital vehicle designs joined the list of competitors. A few were eliminated, some fell by the wayside when, again, funding did not come through. But some stayed the course.. Finally, in 2004, Burt Rutan's SpaceShipOne made it to space twice inside of two weeks to win the Ansari X Prize. And then came Branson.

Now that privately run voyages into space were no longer beyond the horizon of practical reality, changes in regulations became necessary to permit them to fly with insurance that would cover the inevitable accident. At the Federal Aviation Administration, Patti Grace Smith stepped up to the plate and headed up an Office of Space Flight. She and her staff, working at times around the clock, put in place a licensing system the cash-strapped newspace companies could afford.

"When I went to my first launch, I knew that I had found what I was looking for. I could not contain myself," [Patti Grace] Smith recalled. "The opportunity to lead an office where you are laying the groundwork, the policy framework, the infrastructure decisions, the governance, the regulations for a form of transportation that I may not see in my lifetime, but my kids will." – Page 202 |

Branson's company, Virgin Galactic, is now on track to fly passengers out of a spaceport at Las Cruces, New Mexico (although the first flights probably will take place at Mojave, which has a spaceport license now.) Other companies are also pursuing the goal of suborbital flight, and based on past history they will not lack for customers.

The vehicles these companies develop can also serve other markets: useful research can be done in the few minutes of microgravity a suborbital flight provides. Rapid point-to-point ballistic travel is another possibility; many people will pay to get themselves or their high-value packages from, say, Los Angeles to Tokyo in two hours. With second-stage boosters, even launching satellites is not beyond feasibility. However these possibilities work out, we are in for some fascinating years ahead.

This book is part of the series Outward Odyssey: A People's History of Spaceflight. Forty black and white illustrations augment the text. The book contains an abundant, if disorganized, list of sources: 37 books; 131 periodicals and online sources; 58 interviews (through 2009); and 69 entries in a category labeled "Other sources." This last category includes some Web sites and books. More serious than that is the fact that the narrative is disjointed in places. For example, Elon Musk and SpaceX are not mentioned until page 209. Other pioneers in what's come to be known as the "NewSpace" category, like XCOR and Blue Origin, appear much earlier in the book. Also, portions of the story are repeated; an example is that of Dennis Tito and Eric Anderson (pp. 129-30.) And some players are never mentioned. But this book is well worth reading, chock full of interesting space flight history, and it's definitely a keeper. (It is, perhaps, the closest thing to a biography of Robert Truax that will ever appear in print.) I just feel it could have used another editing pass. Despite this, I give it full marks.

To contact Chris Winter, send email to this address.

To contact Chris Winter, send email to this address.