|

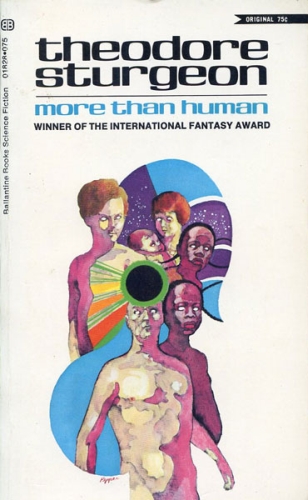

| Cover art by Robert Pepper |

| MORE THAN HUMAN Theodore Sturgeon New York: Ballantine Books, January 19701 |

Rating: 5.0 High |

|||

| ISBN-13 978-0-8240-1438-4 | ||||

| ISBN 0-8240-1438-3 | 188pp. | HC | $0.75 | |

Suppose you had some special ability: not just a talent for math or music or gymnastics, but an ability no one else possessed — something earth-shaking, like the ability to think yourself from place to place: teleportation. What would you do with such a skill? Who would you share it with? Or would you live alone, to keep the secret?

Possession of such a wild talent is a common premise in science fiction. Most often, the characters possessing such a special ability live pretty much like ordinary humans. Sometimes they keep their ability secret, by using it discreetly; other times the difference is accepted, but not always without envy and hostility — much like great wealth. But having such a revolutionary power does not otherwise change the way they think and live.

It was different with Sturgeon. He saw that such abilities take those who possess them out of the realm we understand as humanity. In this tale he conceives a group of remarkable individuals. All can communicate among themselves telepathically, although in a roundabout way in some cases. In addition, one is a telekine; she can move objects with her mind. There is a pair of twins who can teleport. There is an infant of awesome intellect; he can answer any question (but only via telepathy.) And the fifth member of this group has the power of telepathic command. He functions much like the general in a military unit, selecting missions for the group and assigning them specific tasks. But "general" is a poor analogy, for this group functions more like a superorganism. Can the hand mutiny against the head?2

People often say you can't change human nature. But human behavior is the expression of human nature, and human behavior has changed greatly over the past few centuries.

True, the change has not always been for the better; but the trend is toward improvement. The best novels of science fiction — indeed, the best works in all genres of literature — urge us to aspire to improve our behavior by showing us how such aspirations can lead to more desirable outcomes.

More than Human stands proudly in that grand tradition.

When directed by the "head", these individuals can accomplish virtually anything. That is an important factor in establishing their modes of thought; they simply do not have the constraints on behavior normal humans do. Also, they were all outcasts to some degree before before becoming, quite by chance, part of this superorganism, this Homo gestalt And once joined, they find themselves unique: the solitary member of a new breed of human. Their isolation brings a host of perils, both from without and from within. Superhuman powers do not remove human frailties. Or, as one Homo sapiens puts it

Hip said, from the scarred depths of memory, "People all around, you by yourself." He made a wry smile. "Does a superman have super-hunger, Gerry? Super-loneliness?" – Page 185 |

The drama in the novel comes, in the beginning, from the struggles of these individuals to survive and associate, and, later, from the conflict between Hip, a standard but intelligent human, and Gerry, the second "general" for the group. (The first, Lone, died in an accident.) Their conflict is largely on an emotional and ethical plane. That is the story's greatest feature.

"Listen," she said passionately, "we're not a group of freaks. We're Homo Gestalt, you understand? We're a single entity, a new kind of human being. We weren't invented. We evolved. We're the next step up. We're alone; there are no more like us. We don't live in the kind of world you do, with systems of morals and codes of ethics to guide us. We're living on a desert island with a herd of goats!" "I'm the goat." "Yes, yes, you are, can't you see? But we were born on this island with no one like us to teach us, tell us how to behave. We can learn from the goats all the things that make a goat a good goat, but that will never change the fact that we're not a goat! You can't apply the same set of rules to us as you do to ordinary humans; we're just not the same thing!" – Page 170 |

If More than Human has a weakness as a novel, it is the gap in Janie's development. At the end of Part 1 she is a well-functioning member of Lone's group, but still a child. Her growth (and the growth of other members) is implied — with the caveat that Lone will retard such growth. Part 2 is dedicated solely to Gerry's interaction with a psychologist. We see Janie next in Part 3, when she undertakes to rescue Hip from Gerry's "curl up and die" command. Now, suddenly, she is the quintessential Sturgeon woman: skilled at the womanly arts of cooking, cleaning, sewing, etc., and infinitely patient with her man in his time of trouble. So there is merit in the criticism that this novel doesn't hang together as well as it might. However, the three parts of it, considered separately, do hang together. So my opinion is that while Sturgeon might have given us a better novel, we have to evaluate the one he did give us, and my evaluation is that this novel is very good indeed.

More than Human is Sturgeon at his best. It gives us believable characters interacting in plausible ways, and their dilemmas are deeply affecting. Someone once wrote that Sturgeon "gets inside hurt people."

That he does. That he does. Full marks.

To contact Chris Winter, send email to this address.

To contact Chris Winter, send email to this address.