|

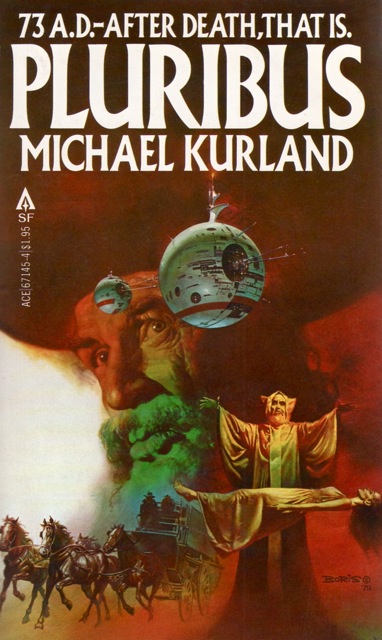

| Cover art by Boris Vallejo |

| PLURIBUS Michael Kurland New York: Ace Books, January 1980 |

Rating: 5.0 High |

|||

| ISBN-13 978-0-441-67145-8 | ||||

| ISBN-10 0-441-67145-4 | 272pp. | SC | $1.95 | |

Eerie is the discovery that this novel by Michael Kurland, which has been in my possession for more than a year, deals with a virulent plague organism for which a vaccine has been developed — and with those who would kill those distributing the vaccine to prevent its use. Now, in December 2020, the real world is coming to the end of a pandemic that, while it is not nearly as virulent as the Death of Kurland's novel, still has plunged America into lockdown and economic depression.

The situation in the novel is far more dire. Some seventy years before, the mutated ECHO virus1 now known as the Death ravaged the human population of Earth. Civilization then was more advanced than ours, as hinted at in the quotation below. Several hundred people had been established on Mars. This enclave, Ley Base, is self-sufficient for the near term and maintains laboratories for biomedical research. To protect them, human contact with Earth has been ended; but radio contact is maintained, by hook or by crook, and carefully sterilized droneships continue to transfer vital cargoes.

With 90 percent of its human population gone, Earth civilization could not survive. Except for carefully protected enclaves of science, mostly at former colleges and universities, the United States resembles eighteenth-century England: an agrarian society of devout, poorly educated folk who depend on animal power to do their farming and are ruled by a collection of nobles.

From prehistory, Pepperidge thought, to posthistory. He found the idea amusing. From prehistory to posthistory in four thousand years. And now, with the breakdown of everything that was civilization, the goblins were indeed returning; coming out of their secure hiding places in the human mind. A hundred years ago, total literacy was an almost realized goal; today only those in the enclaves could read, or wanted to, and nowhere was anyone printing books. A hundred years ago scientists had penetrated to the particles within the particles of the atom, had gazed upon the stars that made up distant galaxies, and had placed men upon other worlds. Today, seventy-three years after the appearance of the Death, "science" was a curse word outside the enclaves, and mostly a memory inside. The atom was once more inviolable, the distant galaxies invisible, and the men on the other worlds were cruelly fated to remain there, barred from returning to Earth by that mutated ECHO virus known as the Death. – Page 41 |

The enclave at Chicago handles communication with Ley Base on Mars. Their dish antenna having been trashed by vandals, they do it with a home-brewed array of aluminum-foil panels set into frames and aligned for Mars passage. The latest message reveals that the Ley base biomed lab has a vaccine — not for the Death, but for an even more lethal mutation that is likely to appear on Earth 20 to 30 years ahead. This message is passed by couriers to the other enclaves. The enclave leaders decide on a risky operation: a volunteer will bring samples to Earth, docking at the decades old, deserted space station and reaching the surface in an equally aged shuttle.

That may not be the riskiest part. Safely on the surface, the vaccine will still be useless if it cannot be manufactured in quantity. This means distributing samples and instructions to enclaves all across the country — a country filled with communities where science is considered a curse — using the most advanced ground transportation available: a horse-drawn wagon.

Leaders at Palisades enclave in California handle the latter part of this plan. As finally conceived, it depends on an old man named Mordecai Lehrer, a longtime itinerant peddler and covertly a courier for the enclaves on the West Coast. We meet him as he drives his mule-drawn wagon into a town and finds it captivated by the trial of a young man and woman kidnapped from the nearby enclave. The sin of these two people, engaged to be married: making love out of doors. The fundamentalists of the town sentenced them to be hanged next morning and put them in the jail.

Come evening, Mordecai sauntered into the jail and engaged the two night guards in a friendly game of rummy — no gambling, of course; playing for points only. He'd brought along a jug of hard cider, which he shared generously. Soon the guards were dead to the world. He found the keys, freed Peter and Ruth, and got them out of town in his wagon. He stayed behind; the wagon had limited space.

The townspeople, mightily peeved with Mordecai, decreed a new trial. It happened that Judge Benjamin Aristotle Crater, Justice of the Fifth Circuit of the Great and Sovereign State of the Independent Duchy of California, was due the next day. He rode into town on schedule, followed by two outriders who would serve as defense and prosecution. They dealt with a number of cases — and last came to Mordecai. The townspeople demanded a jury trial; the jury took ten minutes to find Mordecai guilty. Judge Crater2 sentenced him to not less that ten years at Alcatraz Prison. He was picked up by two men in a horse-drawn police car with wooden wheels the following morning.

Extensive preparations for Mordecai's perilous mission began. His plan was to become a snake oil salesman and stage magician for the journey. (He had to explain "snake oil" to Dr. leLane, and do quite a bit of convincing.) Finally all was ready: a new, large wagon, gaudily painted and provided with suitable hiding places for the kits and instruction manuals — and also with trade goods and sundry tools needed for the journey, including an old shotgun. It even had a spare tire to go with the rubber tires fitted to its four wheels. It would be drawn by two horses, with a third tied on behind.

So Mordecai, Peter and Ruth began their journey to the east. (A medicine & magic show has to have a comely young woman as assistant, after all.)

Meanwhile, Socrates Proudfoot coasted toward Earth in his ship, a box holding carefully packed vials of vaccine in the hold. Eventually he would reach the space station in Earth orbit, dock with it, transfer his precious cargo to the waiting shuttle, and descend to the surface. If he could dock. If the shuttle still worked. If Chicago enclave could give him the proper coordinates and burn times.

As you can well imagine, Mordecai and his companions encounter some hair-raising situations and some hi-jinx along the way. They do make it to Chicago enclave, and Socrates Proudfoot does manage to land the shuttle safely on the long runway at Chicago. But all that is only the beginning of what needs to be accomplished.

Pluribus is well written and tightly plotted. I found no grammatical errors. To me, in a few places, the things Mordecai gets up to seemed over the top, excessively frivolous, for the overall seriousness of the tale. But then I recalled Michael Kurland's body of work, and I reconsidered. This is a very enjoyable tale, worthy of full marks. My only regret is that there doesn't appear to be a sequel.

To contact Chris Winter, send email to this address.

To contact Chris Winter, send email to this address.