|

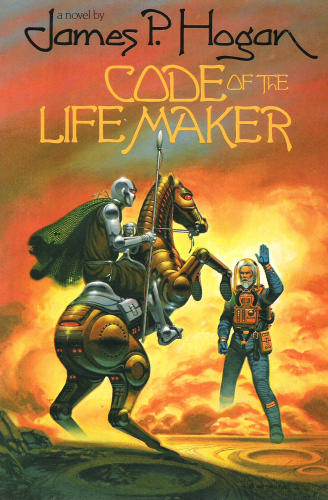

| Cover by David B. Mattingly |

| CODE OF THE LIFEMAKER James P. Hogan |

Rating: 5.0 High |

||||

| New York: Ballantine Books, June 1983 | ISBN 0-345-30549-3 | 405pp | SC | $2.95 | |

A true tour de force and a departure from the mainstream of his novels, Code of the Lifemaker has echoes of Gulliver's Travels about it. But the echoes are dim, and soon fade. A supposed manned mission to Mars really heads for Titan, where earlier, robotic probes had returned brief glimpses of what appears to be a machine civilization.

It develops that the purpose of this mission is to make contact with that civilization and co-opt it to produce manufactured goods to prop up the economy of the Western bloc. (Recall that this was written in 1983, the Cold War.) There are numerous nations on Titan, all roughly at what on Earth would be called medieval level. Kroaxia is a theocracy, with a king who plots to reduce the power of the priesthood; it's apparently an analogue of medieval Spain. Enlightened individuals escape to Carthogia, which is ruled by Kleippur, a prince of a robeing.1 (He may be modeled on Prince Henry the Navigator of Portugal.)2 But enough of Titanian geopolitics. The main thing is that the men from Earth are determined to secure those production agreements, and gladly play one nation against another, even to the point of secretly giving Kroaxia's army modern weapons and training in their use.

Curiously, the stage magician and pretend psychic Karl Zambendorf, sent along to facilitate the introduction of this virtual slavery, develops respect and empathy for the Taloids and determines to throw a monkey wrench into the mission's plan. It's curious because Hogan had set Zambendorf up as the villain of the piece. And his plan, like his stage work, depends a great deal on improvization.

It begins with a lonely mountain peak and a priest on a solitary journey. It begins with the landing of a craft from another world, and the handing to that priest of a tablet, forged in miraculous fire, bearing three commandments. Now, Groork the Hearer becomes Groork the Enlightener. Now, his mission is to somehow convince a disbelieving world that the Lifemakers are here.X

"For many hours the Enlightener preached great words of love and wisdom from a hilltop to the soldiers assembled on the slopes below. When he had finished, they abandoned their weapons in the desert and turned back to return to Kroaxia. The Enlightener was lifted again into the sky to be borne ahead by the angels. He promised he would await his converts at the city of Pergassos, where they would join him to begin together the founding of the new world." "'It's amazing! I simply don't believe this,' Massey said to Zambendorf over the link from the Orion as the flyer climbed higher and transmitted a view of the shambles that had been the Paduan army. 'Just the last phase left now, Gerry,' Zambendorf told him confidently. 'Next stop—Padua. We've rehearsed the cast, tested all the props, perfected our technique, and everything works just fine. What could possibly go wrong?'" – Page 310 |

Throughout this novel, the people who believe in mind-reading, communication with the dead, and similar occult phenomena, are portrayed as clueless and treated with amused contempt. Hogan's feelings at the time about people who are gullible enough to believe in such things are expressed clearly in the final few paragraphs of the novel.

It's doubly ironic, then, that James Hogan, in later life, wandered into what is sometimes derisively called "woo" — denying the reality of Darwinian evolution and such. It was hard to believe, but it is true.

Well, let's see... You have a mission effectively controlled by corporate bigwigs determined to turn Titan into a profit center. You have significant military assets, including Special Forces troops and anti-aircraft missiles, at their disposal. So it's easy to tell what could go wrong. Zambendorf is just running on habitual confidence here.

In the so-called last phase, things do go wrong — although not so wrong as they might. Zambendorf, warned obliquely of the possible use of those missiles, pulls out. Groork, discredited when his promised miracles don't show up, is arrested and sentenced to die. Execution for heretics in Kroaxia means being pushed off a cliff into a vat of acid. But Zambendorf and his team get it together, and at the last minute pull off a literal cliff-hanger rescue.

The story doesn't end there, of course. The ultimate defeat of the corporatists turns on a change of heart by one in their ranks, someone who has a private channel to the international space agency back on Earth.

Hogan skillfully blends the high-tech features with clever rule-of-thumb psychology in a plot with plenty of twists that arrives at a very satisfying ending. This novel earns full marks.

To contact Chris Winter, send email to this address.

To contact Chris Winter, send email to this address.