|

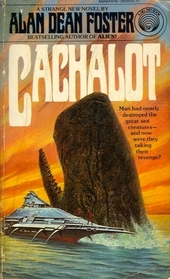

| Cover art by Darryl K. Sweet |

| CACHALOT Alan Dean Foster New York: Ballantine, May 1980 | Rating: 4.5 High |

|||

| ISBN-13 978-0-345-28066-4 | ||||

| ISBN-10 0-345-28066-0 | 275pp. | SC | $2.25 | |

The ocean world of Cachalot1 has virtually no land, only the equivalent of coral reefs that rise within a few meters of the surface atop seamounts. It's normally a languid sort of place; but now there is a menacing submarine mystery. To some of these reefs are anchored floating towns where the sea's biological wealth is extracted and processed for shipment. Lately, four of these towns have been completely destroyed — no one knows by what. There are no survivors. Of the structures and their contents, only fragments remain, and hold no clues.

The requisite team of off-world experts is assembled and brought in. They are the "extramarine" biologist Cora, her daughter and reluctant assistant Rachael,2 and a man named Merced, another biologist.3

Foster dedicated his novel thus:

The theme of saving whales is strong with this one. Foster posits that, about 800 years before his story opens (200 years in our future), a "serum" that let the whales use all of their enormous brains was administered. They soon developed a language and culture. In recompense for our previous slaughter of them, they were given the chance to live on Cachalot. Most accepted. The Agreement of Transfer, concluded 730 years before events in the story, provides that humans shall not interfere with whales, not even to study or converse with them. Cachalot has thus become a cetacean paradise — but for one thing, as this story reveals.

There's some overlap with Star Trek: The Voyage Home, in which whales are also transported through space to save them. That movie, of course, was released in 1986, so there's no question of Foster having cribbed from it. Also, Kirk and Spock transport their whales in order to save 24th-century Earth from a powerful alien probe, since only the whales can communicate with it, and Earth of that period has none left. It's from that movie, the most light-hearted of the Star Trek movies, that I draw the title of this sidebar.

On landing, they immediately begin to encounter Cachalot's complement of exotic alien life forms: they are menaced by the normally placid toglut. But it's driven off by their guide, Sam Mataroreva. They proceed to investigate their problem, but after several days they are no closer to an answer. Even conversing with a pod of standoffish whales provides no useful information. (The whales had been brought from Earth centuries ago, and are thriving on Cachalot; see the sidebar. The great whales wish only to develop without human interference; but orcas are friendlier, and a pair of them frequently help Sam.)

"How Typically Human," the other new arrival agreed. "Dost Thou Believe That Because We Have Gained Intelligence We Are Doomed To Repeat The Mistakes Of Mankind?" "We Have Heard Tales Of Things Like 'War'," the female said. "'Tis Difficult Enough For Us Merely To Imagine Such An Oscenity. The Idea Of Practicing It Is Utterly Beyond Us. Dost Thou Think We Have Gained Intelligence, Improved, And Progressed So That We Might Imitate Thy Stupidities? Contradiction, Contradiction!" Both breached slightly. An enormous volume of water cascaded over the Caribe, drenching its occupants. – Great whales, speaking pompously on page 104 |

By the time they arrive at Vai'oire, a town of some 1,100, they have concluded some sophisticated human agency must be behind the destruction. Then, as they are diving on the other side of Vai'oire's lagoon with Dawn, one of its residents, they witness its destruction — by whales. Left stranded, they survive for days until a boat arrives. The biologists are cheered, but Sam urges caution. It proves a wise precaution as the crew of the boat proceed to scavenge valuable remains from Vai'oire. This reinforces their idea of human involvement. But their immediate problem is what to do about the looters, who must soon discover them.

I won't say how they do get the upper hand. Suffice it to say that cavalry shows up. Soon the looters are in the hands of the authorities, trussed up and headed for trial at Mou'anui, the planet's administrative center. This leads to the story's only failure of continuity; for we are never told how these people, and their captors, end up in jeopardy in its heart-stopping climax. Except for that, the story is tightly plotted, with several twists. The dialogue is mostly good, personal interactions are satisfying, and the sea is filled with suitably weird creatures: the toglut; the great mallost (never seen or heard from); the mollusk teallin ("like a perverted abalone"); and the ninamu pheromonite. All in all, it's a very enjoyable read. I mark it down from the top only because of that one lapse.

Cachalot fits into Foster's Humanx universe, and is the second of his novels in that series after Midworld (1975). The two novels are similar in ecological message — as well as in hints that the creatures depicted as hostile to humanity plan on developing yet more ominous powers.

To contact Chris Winter, send email to this address.

To contact Chris Winter, send email to this address.