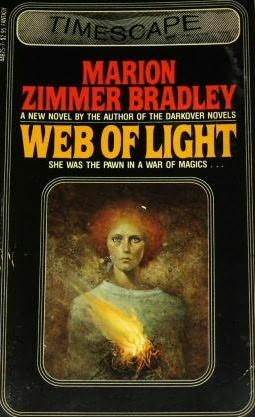

| WEB OF LIGHT Marion Zimmer Bradley New York: Timescape Books, February 1983 |

Rating: 4.0 High |

|||

| ISBN-13 978-0-671-44875-2 | ||||

| ISBN-10 0-671-44875-7 | 208pp. | SC | $2.95 | |

Marion Zimmer Bradley (1930-1999) was one of the more prolific authors of fantasy novels and shorter works. The Mists of Avalon (based on the Arthurian legends) is perhaps her most famous work. She is also known for her Darkover series of 28 novels; other writers continue to extend this series. Marion Zimmer Bradley was also active in fan culture. She was a co-founder of the Society for Creative Anachronism (probably with Poul Anderson.)

Set on an Earth where magic works and priests hold sway, Web of Light is part of her Atlantean series. There is a caste of Priests of Light, keepers of ancient secrets and apparently guardians of moral order in their land; one of them, Rajasta, is a chief character in this tale. There are the Grey-robes: Sorcerers with power over nature. They use this power for good, principally for healing; but their order has been known to harbor Black-robes, evil mages corrupted by the lust for power. Riveda leads the local chapter. And there are women. Chief among them are Domaris, just coming of age, and her younger sister Deoris, both daughters of Talkannon, Arch-Administrator of the Temple of Light.

Newly arrived in the city is Micon of Ahtarrath, an Atlantean of power, now broken by Black-robe torturers. Finding and punishing these Black-robes becomes Rajasta's righteous goal. But Micon forbids vengeance and will not identify them, saying it would interfere with his mysterious goals. Nevertheless, Rajasta pursues justice. As is proper according to his station, the Priest of Light informs Riveda and directs him to investigate his own Grey-robes for signs of corruption. Riveda reluctantly agrees.

...brought to you by Western Union. Fantasy aficionados will not mistake the meaning of that ominous halo of flames, the Dorje, surrounding Riveda's head, nor of the strange apprehension that he seems to inspire in others.

Domaris is an acolyte to the Temple of Light — one of twelve chosen from the comeliest and most accomplished young men and women. Thus she is present with Rajasta on the Night of the Zenith, when portents are read. She meets Riveda for the first time, and experiences an unaccountable apprehension which she conceals. Later that same night, gazing at Riveda, Rajasta in a vision sees his head haloed with fire: the Dorje. But Rajasta puts this evil omen down to a nightmare, convincing himself he has no reason to distrust Riveda.

It reminded me somewhat of Andre Norton's Witch World series. But Marion Zimmer Bradley's work is somewhat slower paced, with more descriptions of countrysides, weather conditions and inward emotions. Also, I doubt that Norton's characters would wave away their dark premonitions like the characters in this novel do.

"Deoris's eyes were thunderclouds: Micon used the familiar 'thou' which Deoris herself rarely ventured—and Domaris did not seem offended, but pleased! Deoris felt she would choke with resentment." Rajasta, his misgivings almost forgotten, smiled now on Domaris and Micon, vast approval in his eyes. How he loved them both! On Deoris, too, he turned affectionate eyes, for he loved her well, and only awaited the ripening of her nature to ask her to follow in her sister's footsteps as his Acolyte. Rajasta sensed unknown potentialities in the fledgling woman, and, if it were possible, he greatly desired to guide her; but as yet Deoris was far too young." – Page 95 |

Marion Zimmer Bradley was known as a feminist writer. That may well be true of her work as a whole; but based on this novel alone I would call her writing feminine rather than feminist. She devotes a great deal of attention to the emotions of her women characters — especially to Deoris, with her moody petulance, her dependence on her older sister. As for Domaris, there are frequent descriptions of how much she adores Micon and enjoys bearing his son. However, Bradley does not mention the actual union of Domaris and Micon to conceive a son; the two-page chapter titled "The Union" is instead about the induction of Domaris into the sacred Order of Light. Two chapters later, "The Secret Crown" shows us Domaris and three other women outdoors gathering flowers for a festival, with a casual breastfeeding scene of one's infant daughter. The crown referred to is not some buried relic invested with magical powers, but Domaris's discovery that she does indeed bear the child, and thus finally wears the crown of true womanhood. This being the case, the lack of mention of her joining with Domaris is puzzling. I'm not calling for a sex scene here, but surely Domaris's attitudes would argue against Bradley leaving this transcendent event entirely undescribed.

All the female emoting and chit-chat goes on for a long time. Attuned as I am to the male model of sword and sorcery tales, I found it slow and boring. But there is some action toward the end of the book: Riveda admits Deoris to a secret Grey-robe ritual, during which she partakes of a dire and unpleasant vision and somehow attempts to injure Domaris and the unborn child. The nature of this attempt is not made clear; we only know it does not succeed. Almost immediately comes the Night of Nadir, when strange chanting is heard from somewhere. It fills Micon with foreboding; he knows its import, and rushes to prepare a counterspell. He succeeds in staving off the summoning of dark forces, but the effort weakens him onto death. He barely survives to confer his powers on his newly born son. In fact, he is unable to complete that ritual and draws on Riveda to do so.1

Thus it seems that Bradley may have been weaving a subtler spell. Riveda may not be the focus of evil in this tale; all those signs and portents2 might have been misdirection. Or perhaps not. I'll have to read the sequel, Web of Darkness, to learn which.

This is a fairly competent work of fantasy invention. However, I did not enjoy reading it; slow pacing for most of the book, the telegraphing of Riveda's villainy (whether misdirection or no), and the several errors of wording (even if mostly an editor's fault) tell me this is not Bradley's best work.3 I rate it accordingly.

To contact Chris Winter, send email to this address.

To contact Chris Winter, send email to this address.