|

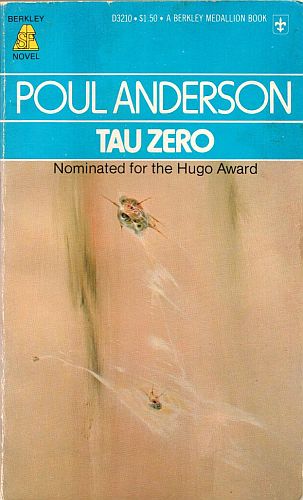

| Cover art by Richard Powers |

| TAU ZERO Poul Anderson New York: Berkley Medallion, September 1976 |

Rating: 5.0 High |

||||

| ISBN-13 978-0-425-03210-7 | |||||

| ISBN 0-425-03210-8 | 188pp. | SC | $1.50 | ||

The ship was magic — a technological magic honed over seven generations including Leonora Christine's own. She was a Bussard ramship, bound for a star 32 light years from Earth where a robot had previously detected planets that might be habitable. She carried a complement of 25 men and 25 women: crew and passengers combined, competitively selected from the best of Earth stock to maintain the ship, explore the planets at their destination, and set up a colony if that proved possible.

Their carefully laid plans did not come to fruition; they met a nebula the robot had not encountered. Tenuous as it was, it yet had enough density to overtax and disable the ship's deceleration system. Repairs could be made, but the ship had attained such a velocity that venturing outside to make those repairs would mean death by radiation. They would have to slow down — and they could not slow down.

One other alternative presented itself: keep accelerating until they reached a space empty enough that the proton flux could be ignored. That meant leaving the galaxy, and ultimately leaving the local group of galaxies. By that time they had attained such enormous velocity that their tau value approached zero. That, together with vision limited by distance, made navigation difficult. Their chances of reaching a suitable destination receded into infinity.

And infinity is where they ended up. They lived at a time dilation such that weeks of ship time meant billions of years outside. The cosmos collapsed around them, falling back on itself into a new Big Bang. Folk fell into despair; only the strongest among them kept functioning. Hope remained: there might be the barest chance of skirting the monobloc, of circling it while it evolved into a new universe with new galaxies and new planets.

Ingrid Lindgren completed her account. "–that is what is happening. We will not be able to stop before the death of the universe." The muteness into which she had spoken seemed to deepen. A few women wept, a few men shaped oaths or prayers, but none was above a sough. In the front row, Captain Telander bent his head and covered his face. The ship lurched in another squall. Sound passed by, throbbing, groaning, whistling. Lindgren's fingers momentarily clasped Reymont's. "The constable has something to tell you," she said. He trod forward. Sunken and reddened, his eyes appeared to regard them in such ferocity that Chi-Yuen herself dared make no gesture. His tunic was wolf-gray, and besides his badge he wore his automatic pistol, the ultimate emblem. He said, quietly though with none of the first officer's compassion: "I know you think this is the end. We've tried, and failed, and you should be left alone to make your peace with yourselves or your God. Well, I don't say you shouldn't do that. I have no firm idea what is going to become of us. I don't believe anyone can predict any more. Nature is turning too alien for that. In honesty, I agree that our chances look poor. "But I don't think they are zero, either. And by this I don't mean that we can survive in a dead universe. That's the obvious thing to attempt. Slow down till our time rate isn't extremely different from outside, while continuing to move fast enough that we can collect hydrogen for fuel. Then spend what years remain in our bodies aboard this ship, never glancing out into the dark around us, never thinking about the fate of the child who'll soon be born. "Maybe that's physically possible, if the thermodynamics of a collapsing space doesn't play tricks on us. I don't imagine that it's psychologically possible, however. Your expressions show you agree with me. Correct? "What can we do? "I think we have a duty—to the race that begot us, to the children we might yet bring forth ourselves—a duty to keep trying, right to the finish. "For most of you, that won't involve more than continuing to live, continuing to stay sane. I'm well aware that that could be as hard a task as human beings ever undertook. The crew and the scientists who have relevant specialties will, in addition, have to carry on the work of the ship and of preparing for what's to come. It will be difficult. "So make your peace. Interior peace. That's the only kind that ever existed anyway. The exterior fight goes on. I propose we wage it with no thought of surrender. Abruptly his words rang loud: "I propose we go on to the next cycle of the cosmos." – Pages 169-170 |

It is an audacious plan, and this is an audacious novel. I doubt it will spoil anyone's enjoyment of the novel if I reveal that the plan succeeds. That is a characteristic of a novel by Poul Anderson. I'll allow the reader to learn the nature of that success.

This theme of challenging the very end of the cosmos is one to which Anderson returned in later works. It occurs in two novels I have read: The Avatar (1978) and Genesis (2000).

Tau Zero was nominated for a Hugo in 1971.1 One of the things that makes it a gripping read is the way Anderson portrays character interactions. He shows us their dark times and how they encourage each other as well as their heroic moments. I noticed perhaps 4 or 5 grammatical errors. But having read a good deal of Poul Anderson's work, I am sure these are due to the editor of this edition. I did not record them. Full marks, and for science fiction fans this is a keeper.

To contact Chris Winter, send email to this address.

To contact Chris Winter, send email to this address.