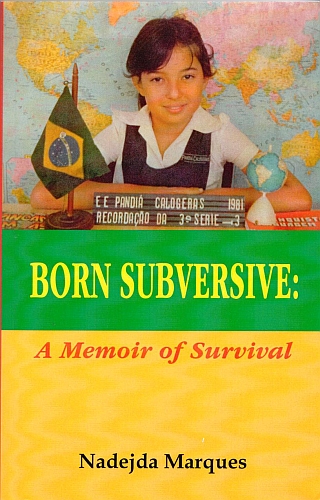

| BORN SUBVERSIVE A Memoir of Survival Nadejda Marques New York: Trofford Publishing, 2008 |

Rating: 5.0 High |

|||

| ISBN-13 978-1-4251-5476-9 | ||||

| ISBN-10 1-4251-5476-X | 166pp. | SC/BWI | $? | |

In the long history of tyranny and injustice, Brazil's dictatorship was nothing extraordinary. Statistics tell us that other countries in Latin America racked up more deaths. Statistics tell one sort of story, but anecdotes tell another. This memoir of Nadejda Marques brings home the futility and pain and terror of Brazil's dictatorship in poignant fashion.

I am a political survivor. Before I was three years old, I had survived two military coup d'etats.1 I had traveled from Brazil to Chile through Argentina, then as a refugee, fled to Sweden, the former Soviet Union and Cuba. It is no surprise that I only spoke my first words at the age of five, when my step-father accidentally dropped me in our bathtup in a former hotel in Havana, Cuba. Only then was I ready to speak.2 *

* * You and I will undoubtedly have many things in common and perhaps you might have lived some of my lives yourself. I am aware that some of these memories do not belong only to one person but because they are not widely accessible and sometimes denied in history books, I rely on your judgment. Perhaps you lived your lives in another time. Perhaps you lived them in another country, and in another language. Of course, there will be a few who will not find any semblance of their lives in them and our perspectives may be light-years apart, but I fear my story is more common than I once thought. There is, however, a good chance that our life experiences complete each other, that perhaps the stories of our lives are different chapters of the same story. That is how I feel. I waited five years until I was ready to speak and now, after more than thirty years, I am ready to write. I hope you are ready to read. – Pages 7-8 & 14-15 |

The generals were determined to modernize Brazil, building nuclear power plants, railways, foundries, irrigation systems, and other basic infrastructure. It was the time of the milagre econômoco, the economic miracle, when annual growth rates exceeded six percent. But wealth inequality also grew, until after ten years most Brazilians were in or near poverty.

Back in the years of the "miracle," however, Brazilians were too distracted by promises that Deus é Brasileiro, God is Brazilian; after all, Brazilians were celebrating that we had won the Miss Universe Contest in 1968 with Martha Vasconcellos4 (since then Brazil has not won the beauty contest again); and its third Soccer World Cup championship in 1970 in Mexico. "If life gives you lemons, make lemonade" and Brazilians, the lemonade makers par excellence, could not see what they did not want to see. Those that differed were clearly subversives. – Page 33 |

Nadejda Marques writes that they also modernized methods of torture.

Her father Jarbas Pereira Marques, a protester, was tortured and murdered on orders of the regime.3 She was less than two years old at the time. Her mother sent her to live with relatives, a pattern that continued for her early life. Her mother remarried in Cuba, a place she describes in glowing terms — praise she later says is partly the product of childhood naivete. But there is no doubt that Cuba was good to her.

Later she returned to Brazil, and then went to Chile, where she was caught up in the Pinochet coup. By luck, she and her parents were among the first to be granted refugee status in Sweden. After some time there, she again returned to Brazil, where the dictatorship was gone but poverty persisted. But although she loved the land of her birth and was delighted to be reunited with her larger family, she began to feel out of place. The anarchy and grinding poverty of the favelas, the brutal raids there by the police, the sense that Brazil was dominated by conformism wore on her spirit. Outstanding work in high school qualified her for admission to United World College. She was assigned to her last choice: the campus in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Arriving in September 1988, she found the United States to be quite unlike the imperialist demon her homeland's propaganda had painted it to be. She made good friends and learned English, a skill that opened the door to many opportunities.5

Back home in Brazil after her two-year term at UWC, she struggled to find a job and help support her family. But, as before, she felt out of place in Brazilian culture, and dreamed of being in some far-off land more to her liking. It didn't help to read in the UWC newsletter of classmates traveling the world. The comparisons to her life in Brazil were stark.

How would they like to read that my younger sister had been in a coma twice in a year? That my brother had been stabbed in the neck while defending a friend in a street fight? That I had been beaten up by street kids when they realized that I carried no money or anything of value? Would it all sound made up? It wasn't. It all really happened. – Page 122 |

She found work as a language instructor and a translator. These two jobs helped, but the family finances were still shaky. Also, she had to finish her college education. (She did, graduating first in her class.) But she contracted pancreatitis, and a botched hospital treatment made her decide to leave that land of abysmal health care as soon as she could.

Eventually she met Jim, the American director of Human Rights Watch in Brazil. She fell in love for the second first time.6 They worked on that issue together, he researching abuses, she reporting them as a "stringer" for the Washington Post. They married and had a child (a daughter, Mara, to whom this book is dedicated.) But then came the terrorist attacks of 9/11, and world attention shifted away from Latin America. Brazil's HRW office had always been starved for resources; now the WP office closed after two years. Eventually Jim transferred to Cambridge, MA. That is where the family lives now. Jim and Nadejda continue to work on human rights issues in places like Angola.

Mrs. Marques has penned a poignant and gripping memoir. The poignancy arises mostly from her unblinkingly matter-of-fact prose style. She shrugs off misfortunes that would break many Americans (at least the white ones.) She has my sincere admiration.

The narrative is a bit sketchy and disjointed in places. Recall her falling in love twice for the first time. Also, her description of the hospital episode seems quite cursory; surely there is more to it. But she writes clearly and well, with very few grammatical errors — a remarkable accomplishment for a non-native speaker of English. Despite the book's lack of an index, I give it top marks and rate it a keeper.

To contact Chris Winter, send email to this address.

To contact Chris Winter, send email to this address.