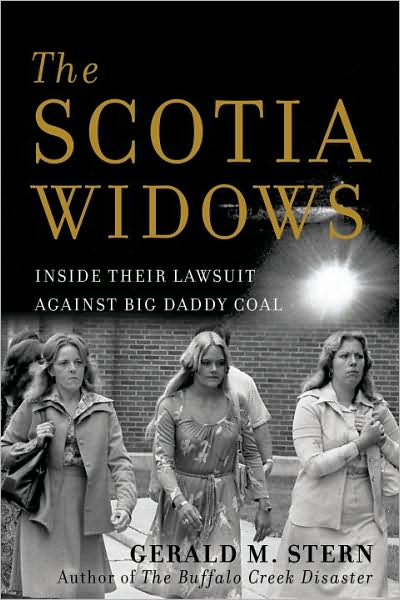

| THE SCOTIA WIDOWS Inside Their Lawsuit Against Big Daddy Coal Gerald M. Stern New York: Random House, 2008 |

Rating: 5.0 High |

|||

| ISBN-13 978-1-400-6764-0 | ||||

| ISBN-10 1-400-6764-X | 145pp. | HC | $20.00 | |

It was long ago — and just last month. Deep in the mine, an improperly ventilated tunnel filled with methane. At some point, an explosive mixture with air was formed, and a random spark set it off. Another bunch of miners died.

In this case, the place was the Scotia Mine in eastern Kentucky, and the year was 1976. Management of the Scotia Mine, determined to open up a new tunnel, shifted two concrete barriers to divert ventilating air down the new shaft. This resulted in no ventilation for the existing tunnel, designated Two Southeast Mains. The company could not wait the month it took to build new barriers. However, they found time to ship a load of steel rails down from outside for future expansion of Two Southeast Mains. Predictably, the unventilated tunnel filled with methane. Just as predictably, the locomotives hauling the rail stirred air into it, and presumably something on one of them provided the spark.

The mine exploded just before noon on 9 March 1976: a cold, dank day. Fifteen miners died. Two days later, eight more died on a rescue mission, along with three inspectors from MESA (the Mine Enforcement Safety Administration.) At that point, the mine was sealed.

"When Blue Diamond's lawyer tried to preclude me from arguing to the jury that 'higher production' and 'lower costs' recklessly led to unsafe mining practices, he claimed, 'Nothing interferes more with production and cost at this mine than this explosion.' I responded, I wish you had thought of that earlier.' Waiting a month or two in order to build the overcasts at the intersection of Two Southeast Mains and Two Left would have stopped production during that time in that one section, and temporarily raised Blue Diamond's costs, but certainly that would have been less expensive in the long run than the subsequent closing of the entire mine for almost a year, the damages they had to pay for the deaths of fifteen men, and the enormous legal fees and expenses they had to pay their lawyers to defend against our civil lawsuit and the government's criminal prosecution." – Pages 139-140 |

What was the Scotia Mine like? Like most every American coal mine, it seems. Stern reports some facts and figures from a congressional inquiry on pages 20-21 (and later):

The report's conclusion: "It was a mine which . . . placed production and profit before the health and safety of its miners."

The litigation began not long thereafter. But it did not conclude for four long years. The Scotia Widows, overcoming some resistance from family members,2 undertook a civil suit against Scotia and its parent company Blue Diamond. A large part of Gerald Stern's eventual success as their attorney flowed from his ability to commiserate with and encourage them. The rest of it came from dogged persistence. His book is a remarkable testament — but, sadly, not a surprising one. It tells of the corruption of the justice system in coal country: the judge in the case (H. David Hermansdorfer is his name) owns land on which coal mining is taking place, hence gets royalties. It develops much later that the sole announcement of this fact is a 3x5 card under the glass of his clerk's desk. He does not recuse himself as the judicial code of ethics requires. Not until the judge rules against him does Stern, as plaintiffs' attorney, discover it — and then only through an anonymous tip over the phone.

I had a feeling something like this conflict of interest would turn up. Hermansdorfer and the defense attorney, Bert Combs, clearly had a good thing going. Between twisting legal rules and precedents to suit themselves, flip-flopping on previous decisions — like arguing Scotia and Blue Diamond were one company, then later saying they were two (with Blue Diamond the "contractor" to Scotia, despite the absence of any contract). Yes, the original trial was quite a circus, and given his performance in it Hermansdorfer was lucky to be able to retire quietly.

"March 02, 2009: I am one of the Scotia Widows and I appreciate Gerald Stern writing a true account of what happened. This actually did happen and there were so many things he didn't put in there. We felt like we were the ones on trial and had actually done something wrong simply because we had moved on with our lives. I was 23 years old with a 22 month old son . . . and I made it!"

"It is a very sad fact that the almighty dollar means more than a human life. Men don't have names. . . just numbers when it comes to a tragedy like this. My heart goes out to all the others who have lost loved ones in a mining disaster. I am overwhelmed when I hear about one and am consumed until I know the outcome."

A Scotia Widow [writing on Barnes & Noble's Web site]

The story does have a happy ending. All of Hermansdorfer's stratagems fail, the case goes to appeal with a sympathetic (read: fair) panel (2 out of 3, anyway), the defense attorney's plea for an en banc panel is denied, and Stern manages to force Hermansdorfer into "offloading" his case, along with two others. The face-saving ploy fooled no one connected with the case. The retrial draws Judge William O. Bertlesman, also a fair man.3 Ultimately Blue Diamond agrees to a settlement which gives each of the Widows enough to live comfortably and provide for her children.

The federal government's prosecution, however, made only the defendents happy. One week before the start of its criminal trial, Scotia agreed to plead guilty on two of five counts. Its punishment, "handed out strongly for penalty and repentance," was a fine of $60,000 to be donated to four charities of its choosing — which donations were tax-deductible. And, as part of Scotia's plea bargain, all charges against Blue Diamond were dropped.

Stern holds nothing back in his narrative; the apprehension that setbacks inspire is on display several times during the course of the trial, and he admits to shedding tears at one point.4 It all adds up to a gripping account with a number of cliffhanger moments. This is not a scholarly work; there are no endnotes and no index. But in this slim volume Stern provides valuable insights into the workings of coal mining and justice in Appalachia. Highly recommended.

To contact Chris Winter, send email to this address.

To contact Chris Winter, send email to this address.