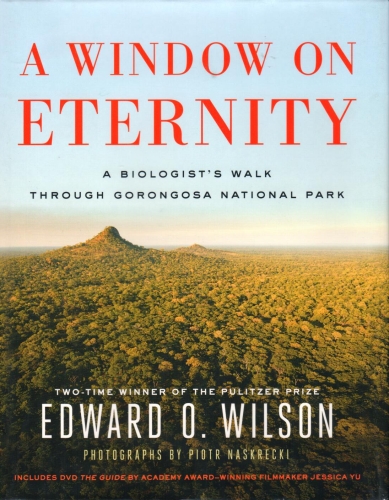

| A WINDOW ON ETERNITY A Biologists's Walk through Gorongosa National Park Edward O. Wilson Piotr Nasrecki (photographs) David Cain (maps) Jessica Yu (DVD) New York: Simon & Schuster, April 2014 |

Rating: 5.0 High |

|||

| ISBN-13 978-1-4767-4741-5 | ||||

| ISBN-10 1-4767-4741-5 | 149pp. | HC/LF/FCI | $30.00 | |

Living in harmony with nature is hard:

A very few societies have evolved to live inside biological reserves with a small footprint, carefully designed to be sustainable. One is the Guarani people living in the northern Argentine state of Misiones. No species of plants and animals are known to have disappeared during their millennium-long residence. Although this achievement is admirable, modern peoples cannot even begin to live in the original Guarani way. It would be painful to endure for even a week. The Guarani way requires an encyclopedic knowledge of the resident plants and larger animals, and all the useful products that can be sustainably drawn from them. It demands care and even management of each species in tun to avoid its extinction. Another necessity is population control... – Page 137 |

In Alan Dean Foster's novel Midworld, humans (presumably from a crashed starship) have become fully integrated into the life of a jungle world.1 They live only in hollows of a certain kind of tree, and each home tree recognizes its tribe. Everything they eat, everything they wear comes from the animals and plants around them, taken only at need. Their tribes have achieved a kind of balance humans of Earth would scarcely recognize, let alone emulate.

Yet there are approximations to such balanced existence on Earth today. Dr. Wilson writes of one, the Guarani (see the sidebar.) But, as he explains, their ways are not for us; we are both too numerous and too wedded to technology — not just cell phones and computers, but the more basic artifacts: motor vehicles, indoor plumbing, electric lights, air conditioning and central heating. We also would have trouble preparing our food from scratch.

No, our path to survival demands not that we renounce technology and revert to primitive lifestyles, but that we embrace and understand technology and use it in ways that minimize its environmental harm. You may hear it said that it is impossible to stop using fossil fuels immediately, and this is extremely true; but the only people who propose this are the ones who use it as a scare tactic in defense of the status quo. It is quite possible to phase out fossil fuels over several decades, and this policy has been proposed for several decades, only to be met by persistent obstruction.

Of course there will be some sacrifices involved. But then, there are sacrifices involved in packing up and moving from one city to another, and in learning to get by with a lower income (or no income.) A great many Americans have made those sacrifices during the past ten years, with little complaint. It does seem ironic that the most vociferous complaints come from those who have the most, and concern minimal reductions in their wealth or status.

But I digress. Habitat loss is the primary cause of extinctions. Therefore, ecological survival will require reserving some tracts of land connecting our present wildlife refuges: national parks and the like.

"During the past one hundred years, human modification of rivers, streams, and lakes in North America alone (mostly through damming and pollution) has caused the extinction of at least sixty freshwater fish species. Our environmental domination of the land and sea has reduced Earth's biodiversity through the extinction of at least 10 percent of its plant and animal species, mostly in the last century. It is driving species at an accelerating rate through conservation biology's descending categories of "threatened," "endangered," critically endangered," and, finally, "extinct." If this perception seems overstated, consider one of the soundest principles of ecology: the number of plant and animal species sustainable in a habitat increases with the area of that habitat (or decreases with the loss of it) by roughly the fourth power of the area. When, for example, the habitat is reduced in area by 90 percent, the sustainable number of its species is cut in half." – Pages 125-6 |

Dr. Wilson proposes a sort of box roughly paralleling the borders of the United States. Of course, this would require interstate and international agreements for full effectiveness. Some progress has been made; he notes that Florida is assembling a corridor from the Everglades north to the Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge in Georgia. He also mentions the Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative, which aims at a continuous path from Yellowstone National Park to Canada's Yukon Territory.2

Dr. Wilson does a good job of explaining why preserving such contiguous tracts of wilderness matters for both practical and ethical reasons. In short, they are vital to our long-term survival.

To contact Chris Winter, send email to this address.

To contact Chris Winter, send email to this address.