| OVERSHOOT How the World Surrendered To Climate Breakdown Andreas Malm & Wim Carton London: Verso, October 2024 |

Rating: 5.0 High |

|||

| ISBN-13 978-1-80429-398-0 | ||||

| ISBN-10 1-80429-398-9 | 401pp. | HC/GSI | $29.95 | |

The authors report that, following the forced reduction of GHG emissions in 2020 and 2021, due to the pandemic, investments in facilities for extracting and transporting fossil fuels surged.

Computer models of climate aim to forecast the temperature, or some other physical quantity, in accordance with natural laws. No aspect of society concerns them. The risks to society, though, are the object of the exercise, and these risks turn on economics as well as physics. Enter the Integrated Assessment Model, or IAM. Typically, it depends on classical economic theory: actors are completely rational and the least costly mitigation method is best. In addition, the default assumption is that future societies will be wealthier and thus less burdened by whatever mitigation method is deemed necessary.

A policy would come out on top of the algorithms not by dint of being superior in some other respect — say, ecologically or ethically or aesthetically preferable — but exclusively on its cost-minimising merits. And cost was assumed to fall over time. Because growth will make future generations richer than the present, a price hike of one dollar will mean less to them than to us; their wallets will be bigger than ours, and so they can better afford any given burden of mitigation. Costs close to the present must therefore be weighted higher than in the future. With this practice of "discounting" embedded in ther code, the IAMs were tilted to postpone emissions cuts: most cost-efficient would be to place them in a wealthier hereafter. And because technologies will also continue to get better and better, costs will fall deeper still, the postponement extended. Ruled out were fast, deep, sweeping cuts starting immediately — a "revolutionary overhaul of the system", in Anderson's parlance, could not be fitted into these models any more than a mass demonstration into a bedroom. – Pages 58-59 |

In addition, the authors point out that the IAMs underestimated how much renewables — especially solar — would drop in price.

No modellers had counted on anything like the trends observable IRL early in the century. All proceeded on the assumption of a price descent so modest and slow as to deviate from a reality racing ahead: the cost for solar panels modelled for the year 2050 was higher than that actually observed in the late 2010s. The same held for concentrated solar power and offshore wind. *

* * Some critics have suggested that "interests from industry" lurked in the underrating of renewablea, but if so, their influence was obscure and uncertain, largely because of the opacity of the IAMs. Rarely if ever did they disclose their parameters. The capacity for self-criticism and correction remained limited: despite the miscalculations being well-known from at least the late 2000s, the IAMs persisted, for reasons again murky, in predicting unreasonably high prices and low penetration of PV in particular. Further research would have to determine if this capital protection was active or passive in nature, or a mix of the two. But capital protection it was. The effect of the error was to make mitigation look far more expensive than it needed to be. – Pages 194-195 |

The year 2022 was a bonanza for fossil fuels across the board. Total profits in this circuit of capital were estimated at 4 trillion dollars, about the same as the GDP of Japan, the third-largest economy on Earth — but this being the sum of profits, not product or income, over the course of only twelve months. Now what does a capitalist corporation do with a profit? It showers its owners — the shareholders — with the money it has made. But not all of it. Some is also poured back into expanded reproduction. A Fossil Fuel FrenzyNot one more pipeline could be built if the world were to avert warming by more than 1.5°C. But in 2022, there were 119 oil pipelines under development — planned, under construction, nearing completion — with a total length of some 350,000 km, enough to encircle the globe at the equator more than eight times. Not one more gas pipeline could be added: but in 2022, there were 477 in progress, with a combined length girdling this planet twenty-four times. Over 300 liquified gas terminals were in the works. Not one more coal mine or plant could burden the Earth, but underway were 432 new mines and 485 new plants. These fossil fuel installations were in preparation already before the scale of the bonanza of 2022 became clear — expanded reproduction is the modus operandi — and with all the capital accumulated in that year, even more were spawned. "We will continue to invest in our advantaged projects to deliver profitable growth", ExxonMobil declared, an ambition so generic for a capitalist corporation as to be bland. Here the new Golcanda was Guyana, in whose territorial waters ExxonMobil first struck oil in 2015. One well after another then came gushing out of the seabed, accounting for one-third of all discovery worldwide in the next seven years: abundant, cheaply produced crude, grabbed through hoodwinking and arm-twisting of the third poorest country in the Western hemisphere (after Haiti and Nicaragua). And there was no end in sight. "The resource base, as you know" — CEO Darren Woods turning to a gentleman from Wells Fargo — "continues to grow. We continue to make discoveries." Gas in Mozambique was another mother lode, and then there was, of course, the Permian Basin, Eldorado of fracking, where, as of 2022, ExxonMobil planned to ramp up production by some 70 per cent in five years. In that year of historic profits, this company boosted its spending on new oil and gas projects by at least one fourth. So did Chevron. Together with ConocoPhillips, these were the companies most assertively writing up their investment plans, spearheading the expansion of the expansion — Aramco, far ahead in absolute terms, advancing one notch slower. It was as if the scenes playing out in Madagascar, Pakistan, Nigeria, the Horn of Africa, Iraq, even Australia and Italy belonged to a parallel universe. No feedback connected them to the calculi of oil and gas companies. The latter proceeded in the most studious conceivable disregard of the lives destroyed around them, not to mention the signal from the UN and scientific bodies and sundry other institutions to start winding production down. It was not heading downwards: production was on the up. Pouring more capital back into it implied output spiking in the years ahead. Even before 2022, ExxonMobil aimed at increasing oil and gas production by 8 per cent in 2027, Chevron by 16 per cent in 2026, Aramco by 16 in 2027, Total by 13 in 2030, Petrobras by 15 in 2027 . . . every company of status carrying a portfolio presuming demand, prices and lifetimes far outside the pathway leading to 1.5°C. Indeed, a range of projects presupposed so much room for oil and gas that they could fit only into an envelope exceeding two and a half degrees. The jewel in the Guyanese crown, a sprawling complex of many dozens of wells, subsea cables and pipes connected with tankers; the deep-water fields off Libya picked up by Italian supermajor ENI; gas in the shallow waters of Angola (Chevron) and Malaysia (Shell); the sweeping exploitation of the oil reserves in and around Lake Albert launched by Total — these were some of the most far-out projects on the stocks. The oil and gas major that made the most aggressive move beyond the 1.5°C pathway in 2022 was Total of France. On 1 February of that year, the "final investment decision" — the moment when capital is definitively dedicated to a venture — was ceremoniously announced for the East Africa Crude Oil Pipeline, or EACOP. It would become the longest heated oil pipeline in the world. Stretching from the fields around Lake Albert on the border of the Democratic Republic of Congo, through Uganda and Tanzania to the coast, it was designed to cross 230 rivers, bisect 12 forest reserves, run through more than 400 villages and displace or otherwise severely affect the lives of around 100,000 people — many already ordered to cease growing crops and repairing their houses — all for the purpose of carrying 216,000 barrels per day to the world market. The resultant emissions would be twice those of Uganda and Tanzania combined. Not satisfied, Total "expressed an interest" in also accessing the oil stored in the peatlands of the Congo Basin. And in May 2022, the Democratic Republic notified the industry that auctions would indeed be held for blocks in its rainforests, posting a slick video on Twitter — here was the new destination for oil investments — tagging Total and Chevron. Still not satisfied, Total was rummaging through Namibia, where it claimed to have found " a potential new golden block", and Suriname; but the French aggressor clearly focused on the African frontiers. So did ENI, from the old Italian haunts of Libya in the north to Angola in the south. The continent supplied more than half of the oil and gas produced by the company; likewise armed with record profits from 2022, it went out to find more. For majors like these, the acceleration of 2022 merely intensified a trend at work since the mid-2010s: growing capital expenditure on oil and gas (except for the pause of the pandemic); a growing share of earnings from their production; growing not shrinking reserves. But the bonanza looked set to induce a change of gears. This could be discerned at the scale of countries as much as companies. The scramble for African hydrocarbons picked up speed after the invasion of Ukraine. Seeking gas supplies to supplant Russia, Europe shopped around in its former colonies and incited Mozambique, South Africa, Morocco and Tanzania to embark on extensive construction of pipelines and terminals geared to the north. The moment was even ripe for dusting off the four-decades-old idea of stiching together a pipeline taking gas from the Niger Delta through the Sahara all the way into the Metropoles of Europe: in July 2022, a memorandum of agreement was signed by Nigeria, Niger and Algeria for this mother of all pipelines. Before the year's end, Nigerian welders were reportedly busy at work. "European countries would like to see the project up and running within a maximum of two years," one Algerian source explained the rush. The State of Israel rode the same wave; in October, propelled by a deal with the EU, its flagship Karish gas field (in waters claimed by Lebanon) came online. It was the first time this state was elevated into a fossil fuel exporter of note. From a Europe at war with Russia, the stimulus to erect brand new infrastructure spread to the four corners of the Earth. Inside Europe itself, Germany, its powerhouse, went on a building spree, pipelines and floating terminals laid out along the coast to accommodate the imports. There was nothing temporary about the commitments. When Qatar and ConocoPhillips signed a contract with the Bundesrepublik for gas deliveries to start on 2027 and continue for fifteen years, Robert Habeck, "minister for economic affairs and climate action" — representing the Greens — thought "fifteen years is great". Come to think of it, he says, "I wouldn't have anything against twenty-year or even longer contracts", running towards and beyond 2050, that is. Unlike Germany, the UK had oil and gas fields of its own to resort to: it took a plunge deeper into the North Sea. In October 2022, the BBC matter-of-factly reported that Westminster had opened a new licensing round for companies. "Nearly 900 locations are being offered for exploration, with as many as 100 licenses set to be awarded. The decision is at odds with international climate scientists who say fossil fuel projects should be closed down, not expanded. Shell and BP jumped at the opportunities. Shell had earlier withdrawn from the Cambo oil field outside the Shetland Islands, a target of protest activity; but this asset was snapped up by Ithaca Energy and scheduled to open in 2025 and peak in 2029 and carry on until 2053. (An up-and-coming actor in the North Sea, Ithaca Energy was based in Tel Aviv — one more sign of Israeli presence on the front — but entered the London stock exchange in 2022, in the largest flotation of that year.) Another of the northern sea beasts to be awakened in the 2020s was — ironical intention unclear — named Tornado. (An oil field in the Gulf of Mexico that went online in 2021 was also named Tornado.) Westminster promised to "max out" the reserves in its part of the sea. And then there was Norway. The biggest producer of oil and gas in Europe (Russia excluded) barreled forward, always on the lookout for fields to get richer. During the decade leading up to February 2022, Norway awarded as many licenses for exploration (700) as in the preceding half-century, making this not only the biggest producer but the most aggressive hunter among European countries. And in March of that year, the government invited bidders for another round of licenses, "including previously unexplored acreage in the Arctic" — how could it not? In his letter, the energy minister clarified that "access to new, attractive exploration acreage is a pillar in the government's policy for further development of the petroleum industry"; and when the round concluded with 47 more licenses awarded to said industry, he praised it for contributing "large revenues" and "value creation". The biggest producer of oil and gas in the world — the US — sped down the same road. It scurried to feed Europe with gas after the outbreak of the war. During the first half of 2022, after only six years in this race, the US overtook Qatar and Australia to secure a position as the world's foremost exporter of liquified fossil gas. It accounted for nearly half of export capacity under development. In the early days of the invasion, the organisation lobbying on behalf of US companies in this business submitted a wish list to the Biden administration — more drilling on public lands; expedited approval of pipelines and terminals; the construction of "virtual transatlantic gas pipelines" — and then jubilantly saw it come true within half a year. That same administration handed out 307 leases for oil and gas exploration in the Gulf of Mexico in 2022 alone (Chevron bagged the most.) The Permian was booming again. No other country in the world had more oil and gas reserves in the development stage — three times the amount in Qatar, four that in Saudi Arabia, six in Canada. Of all the oil and gas expansion by then scheduled to take place until 2050, this single country accounted for more than one-third (twenty-five times more than Saudi Arabia). Here, more than ever, was the hegemon of hydrocarbons. – Pages 12-17 |

The above lengthy passage demonstrates conclusively that fossil-fuel interests worldwide are determined not only to fully exploit those sources that are already productive, but to expand extraction essentially without limit. The authors provide quotations from top executives at these companies who say exactly that — on the record. Meanwhile, the IAMs — as shown in the sidebar — persistently overpriced renewables. Whether this was intentional is unclear. Yet mounting evidence shows that the use of fossil fuels will only grow. More and more, it seems that only some extraordinary event such as a popular uprising can slow or stop the headlong rush past the vaunted 1.5°C limit. Round and round we go, and where we stop, nobody knows.

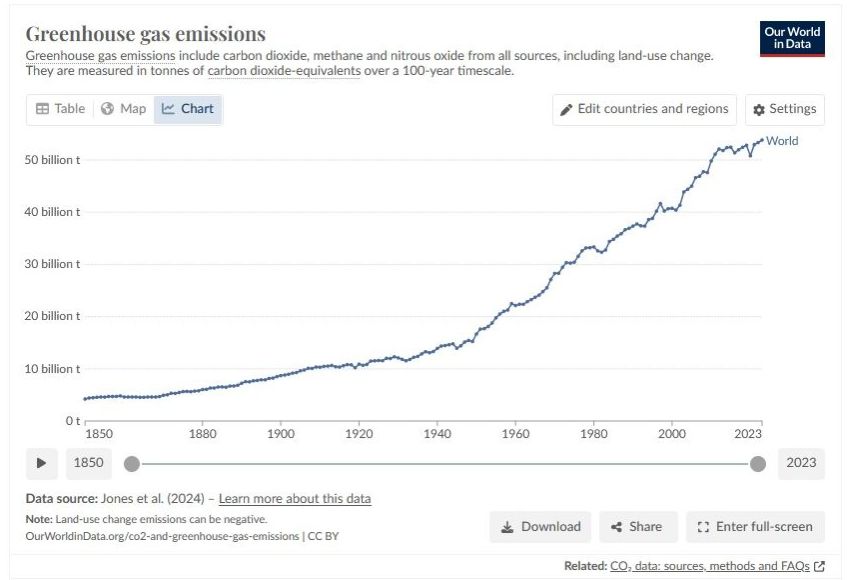

Emissions of greenhouse gases are driving the current warming of our planet. The principal culprit is carbon dioxide (CO2) from burning fossil fuels and from land-use changes, followed by methane and other gases. The world has made some progress in slowing the growth of these emissions by developing wind, solar, nuclear and geothermal power, and by substituting the use of natural gas for coal in places.

However, except during periods of distress like the Great Recession of 2008 or the coronavirus pandemic of 2020, net worldwide emissions of greenhouse gases have continued to rise.

|

| See the original source at this link |

Again, there is less reason year by year to expect that corporations and politicians worldwide will choose to reverse this trend.

Worsening heat waves in 2015 motivated nations of the Global South to ask, at COP21 in Paris, for the IPCC to research and write the Special Report. Overcoming the objections of the US, it did so. Here, the authors summarize the report's conclusions.

The Special Report on 1.5°C duly appeared in 2018. The question it set out to answer was essentially the following: what difference does it make if warming stops at one and a half degrees, compared to two (or higher)? Is 1.5°C something more than a number on paper? Does it correspond to a real break in natural systems, for which it is a convenient shorthand? The IPCC answered in the affirmative, roughly in line with "1.5°C to stay alive". In its examination of the "avoided impacts" if warming were to be capped at that level rather than 2°C, the Panel found markedly lower risks: destructive downpours, protracted droughts, crop failures, water scarcity — all found be less frequent and devastating. Some of this writing had a platitudinous quality to it. If you plunge a kife into someone's abdomen, It is less bad to stop at five centimetres than at ten; similarly, global warming will be less deadly at earlier stages of progression. This goes for all its aspects, with one significant exception: if the warming is mild and slow, bats, rodents, monkeys, and other mammals will have time to move and keep track of their preferred climate, migrating in droves, crossing paths, exchanging the parasites and pathogens that ride on them. They will also brush by human settlements and shed some of their viruses, massively increasing the risk of zoonotic spillover of the kind that caused Covid-19. But if warming is brutal and swift, these mammal populations will simply die off. On this one count — the exposure of humans to viruses from animals on the move — things would be worse at a plateau of 1.5°C than in an ascent to 2°C, which is to say, conversely, that the latter would be all the worse for biodiversity: doubling the extinction rate for plants, insects and vertebrates, as their habitats would be swept away for good. The Special Report identified a particularly stark before and after for coral reefs. In a 2°C world, heat stress would kill 99 pr cent; staying at 1.5°C would save at least one and possibly three tenths of the corals. Some would say that should be reason enough. – Pages 40-41 |

But here we are. Things have only gotten worse. Allow me to offer the briefest of summaries for 2024: It was the hottest year on record in the US, and for many places the wettest. After a wet winter, the west was very dry. It suffered worse wildfires than in prior years. There were 27 weather events that each cost more than $1 billion: the second highest number for a calendar year. Their total cost was $182.7 billion, the fourth highest ever. There were 11 hurricanes in the Atlantic basin (tied with 1995 for fifth highest on record) and 1,735 tornadoes. Finally, the U.S. Climate Extremes Index (USCEI) for 2024 was more than double the average value, ranking highest in the 115-year record.

You can discover more detail in the reports published by the federal government on 10 January 2025.1 You should hurry, because the Trump regime took over ten days later and moved swiftly to excise all data it dislikes, including that relating to climate change. Its declared intention is to boost fossil fuels and suppress clean energy.

To contact Chris Winter, send email to this address.

To contact Chris Winter, send email to this address.