| THE SIXTH EXTINCTION An Unnatural History Elizabeth Kolbert New York: Picador, January 2015 |

Rating: 5.0 High |

|||

| ISBN-13 978-1-250-06218-5 | ||||

| ISBN-10 1-250-06218-7 | 319pp. | SC/BWI | $16.00 | |

The history of science is in large part a series of bad guesses about the natural world. Often these guesses are defended with vigor, even with rancor. One such battle occurred over meteor craters, which until the early twentieth century were held to be volcanic in origin.1

An even more heated and protracted battle involved catastrophism, the theory that Earth's geological history contained sudden disasters, versus uniformitarianism, the belief that change always occurred gradually over vast periods of time. It is this battle that Elizabeth Kolbert explores in her latest book. A French scientist named Cuvier first understood that fossil bones were of animals that had gone extinct. To explain this, he proposed the idea of catastrophes in prehistory.

"All these facts, consistent among themselves and not opposed by any report, seem to me to prove the existence of a world previous to ours," Cuvier said. "But what was this primitive earth? And what revolution was able to wipe it out?" – Page 30 |

Cuvier was met with scorn. But the dispute, as with all disputes in science, was finally resolved in favor of the actual evidence. That showed that both views have merit, but neither is entirely correct: Earth has undergone long periods of gradual change punctuated by abrupt upheavals. Best known among them is the event that left what we call the Chicxulub Crater east of the Yucatan Peninsula. This was a strike 65 million years ago2 by a large asteroid; it left a crater 100 miles across and probably killed 75 percent of all species then living.3

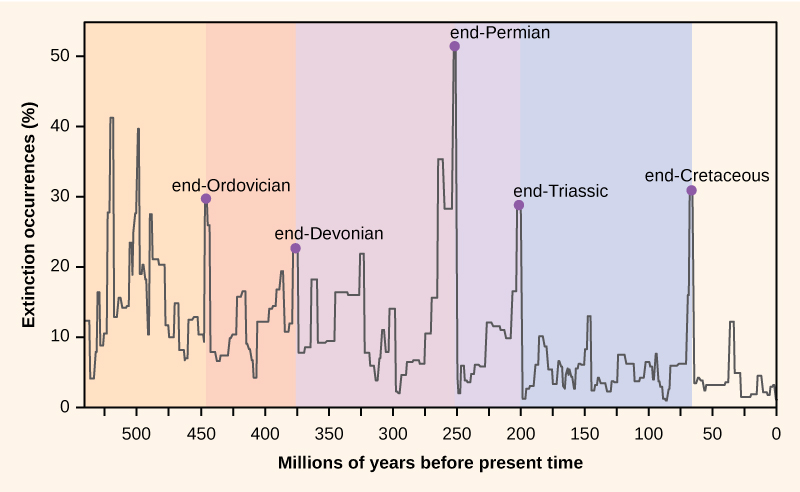

Yet it is not the worst extinction we know about.4 Such extinction spikes are known from the fossil record, where the number of species abruptly plunges and then slowly recovers, with many new forms replacing the previous ones.

It does not require a cataclysm to cause extinctions. They occur throughout time at a relatively steady rate called the background rate. But sometimes, for various reasons, the rate spikes up enormously. Dozens of such spikes are known from the fossil record (see the chart at left), but only five are called Major Extinctions. The most recent cause was Chicxulub. Causes of earlier extinctions are less clear. The Great Extinction, at the end of the Permian Period, is presumed to have been caused by widespread volcanic eruptions over a span of perhaps 10 million years. These would have raised the CO2 levels in the atmosphere, and thus the temperature and sea levels.

Very, very occasionally in the distant past, the planet has undergone change so wrenching that the diversity of life has plummeted. Five of these ancient events were so catastrophic that they're put in their own category: the so-called Big Five. In what seems like a fantastic coincidence, but is probably no coincidence at all, the history of these events is recovered just as people come to realize that they are causing another one. *

* * If extinction is a morbid topic, mass extinction is, well, massively so. In the pages that follow, I try to convey both sides: the excitement of what's being learned as well as the horror of it. My hope is that the readers of this book will come away with an appreciation of the truly extraordinary moment in which we live. – Page 3 |

More like our current situation is the PETM (Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum) at 55 myA. Comparison of conditions then with what's happening now is relevant to our future climate.

| Source: Concepts of Biology |

|

The story is one with profound implications for our present age. It tells us that rapid changes in environmental conditions can devastate whole ecosystems. Humanity has now become a geological force; we are overrunning the surface of the land, overharvesting the life of land and sea, and altering the composition of the atmosphere. The changes we are making will not be as sudden as an asteroid impact, but they are still rapid in comparison to the ability of most species to adapt. The implications for biodiversity are ominous.5

"Today, amphibians enjoy the dubious distinction of being the world's most endangered class of animals; it's been calculated that the group's extinction rate could be as much as forty-five thousand times higher than the background rate. But extinction rates among many other groups are approaching amphibian levels. It is estimated that one-third of all reef-building corals, a third of all freshwater mollusks, a third of sharks and rays, a quarter of all mammals, a fifth of all reptiles, and a sixth of all birds are headed toward oblivion. The losses are occurring all over: in the South Pacific and in the North Atlantic, in the Arctic and the Sahel, in lakes and on islands, on mountaintops and in valleys. If you know how to look, you can probably find signs of the current extinction event in your own backyard." – Pages 17-18 |

As in her previous work, Elizabeth Kolbert provides here a well-written and compelling account of what has been learned about extinction events of the past, and what researchers — in the mountains of Peru, on the Great Barrier Reef, down inside caves in the Adirondacks — are learning about our ongoing extinction event.

Along with an informative text, she gives us black-and-white pictures from her travels. There are extensive endnotes, a bibliography with 215 entries, and a good index. My rating: Top marks and a definite keeper.

To contact Chris Winter, send email to this address.

To contact Chris Winter, send email to this address.