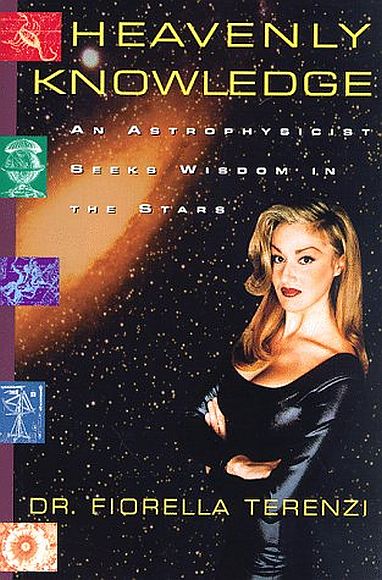

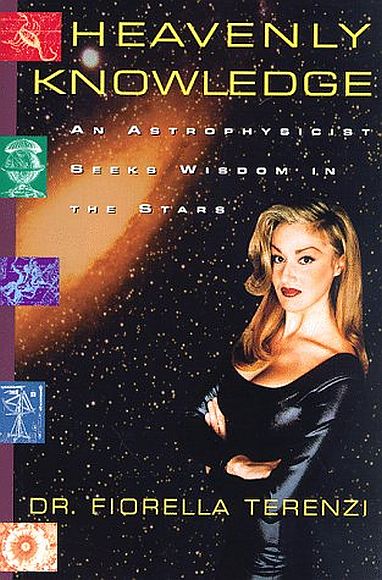

| HEAVENLY KNOWLEDGE: An Astrophysicist Seeks Wisdom in the Stars Fiorella Terenzi New York: Avon Books, 1998 |

Rating: 3.5 Fair |

|||

| ISBN-13 978-0-380-97412-2 | ||||

| ISBN 0-380-97412-6 | 196pp. | HC/BWI | $22.00 | |

This is the story of a little girl who walks one day with her grandmother Angela through the verdant countryside near Milan. Suddenly Angela points to the heavens and exclaims, "Guarda! Look! That star! The brightest one — she is looking at us!"

The girl laughs. But then, peering at the scintillating point of light, she does feel its gaze upon her. Awareness expands. Confronting that vast vista, she feels a oneness with the Cosmos, exalting and humbling at the same time, an intimation of hidden mysteries and meanings waiting to be discovered.

That moment on the Milan hillside lives in her to this day. Clearly it was for her the defining moment of her life. Driven by curiosity about that starry realm, she would dedicate her life to uncovering its mysteries, to elucidating its meanings for the life of humanity.

The little girl, whose given name was Fiorella, grew up to be a beautiful woman and an astrophysicist. In the course of earning her doctorate at the University of Milan1, she came to the conviction that there was something wrong with science. As she puts it:

Not until centuries later [than Plato], when science separated from philosophy to become a purely empirical enterprise that examined objects, measured them, charted their movements, and predicted their future behavior, did astronomy separate from purely human concerns. From then on, studying the stars had to be done dispassionately. After all, this was science—we dared not let our feelings and yearnings and personal quandaries become entangled in examining these celestial phenomena. We must be objective, the new scientists implored us. Our job is to master the universe, not to commune with it. Yet here I sit, my eye fixed to a giant, state-of-the-art telescope, convinced that we can do both—objectively learn about the universe and commune with it. And as the 20th Century draws to a close, I believe it is high time we started some serious (and joyful) communing with the universe. I believe it takes a woman scientist to show us how to combine these seemingly opposite approaches to gazing at the stars. There is a growing campaign among my female colleagues in all of the sciences to give a human perspective to our work, to create a science that aspires to cooperate with Nature rather than to only quantify it. As the philosopher Mary Tiles says, we seek a science "which learns more by conversing . . . with Nature than by putting it on the rack to force it to reveal its secrets, a science of Venus rather than a science of Mars. – Pages 8-9 |

So motivated, she studied astrophysics and radio astronomy by day at the University, then rushed off to the Conservatorio G. Verdi in the evenings to learn about opera and composition. She also read widely in history and philosophy. Her quest: to meld mathematics and music, science and soul; to reunite reason with passion. One summer day, these disparate threads wove themselves into a pattern and she reached another epiphany: The radio emissions from celestial objects could become song!

Proving this thesis led her around the world, to the University of California at San Diego and its Center for Music Experiment. Accomplishing the task took immense effort at data collection, recording gigabytes of numbers representing the signals from energetic objects like UGC 6697, and months of work with the UCSD supercomputers: research, coding, testing, debugging. Finally, everything was ready. Unwilling to face the melody (or, it might be, the cacaphony) alone, she called in some colleagues. When she pressed PLAY, everyone in the small group stood rapt at the otherworldly beauty of the sounds that had, in a very real sense, travelled 180 million years to reach them.

Thus empowered, she gathered up her notes, reports and presentation materials and flew home to Milan to defend her dissertation. After three tense hours of waiting, she heard the results of the review board's deliberations: "Congratulations, Dottore Terenzi." The first phase of her mission was accomplished — and everything changed almost at once.

She kept experimenting with the celestial music she had revealed. One day, her work was overheard by someone from the recording studio next door. That led to a recording contract with Island Records and a CD called Music from the Galaxies. Ultimately she decided to give up her beloved teaching position at the Liceo Scientifico Marangoni in order to reach a wider audience. With characteristic elàn, she plunged into the life of an "astrophysicist-musician" — cutting CDs, performing in concerts2 around the globe, giving interviews and lectures, presenting scientific papers, and of course writing this book.

The book is not well-organized. It consists of an essentially stream-of-consciousness narrative by il Dottore recounting the progress of her mission so far. In that narrative, descriptions of events and flights of fancy are interleaved, the flights of fancy presented in italics and slightly narrower columns to distinguish them. Except for the first, the events she recounts from her personal life are prosaic. We learn that Fiorella: studied astrophysics and music; combined these pursuits in what she calls "Acoustic Astronomy"; earned her doctorate; wrote the chapter on radiation for an Italian physics textbook; taught at the Liceo; made a popular CD; gave up teaching; and became a lecturer and recording artist. From this point forward, it's all about relationships and the problems they engender. Fiorella tells us about her friends' problems with men, problems which her unique access to the wisdom of the Cosmos is often able to help the friends resolve. About her own personal life, she tells us little. We learn that she was friends with Timothy Leary, and wrote some poetry with him. (The book presents one poem.) She hints that there is a special man in her life. A few snapshots of Fiorella going about her activities, and one of Grandmother Angela, appear. This paucity of personal pictures reflects a lack of significant personal events in the narrative. Her professional contributions also seem scanty; there's no list of publications3, no mention of conferences attended or other activities typical for professional scientists.

The flights of fancy, by contrast, are vibrant with imaginative and emotional detail, even steamy in places. Fiorella obviously has a rich fantasy life. Ascerbic comedian Dennis Miller's description of her as "a cross between Carl Sagan and Madonna" is not far wide of the mark. It might be still more apt to call her the astrophysical Dear Abby, because in the end it seems that stars and galaxies, nebulae, quasars and pulsars are merely metaphoric solutions to problems of human relations.

The smooth flow of the narrative is interrupted by pictures and descriptions of astronomical objects: the Crab Nebula, the Andromeda Galaxy, and many more. In most cases, they appear where they are mentioned in the text. I found them distracting nevertheless, because each takes up one or two entire pages even if it does not need all that space. (Occasional descriptions, like that of UGC 6697, have no picture and consume just part of a page.) There are pictures of historic sites: Stonehenge, Angkor Wat and Yaxchilán. (The captions of the latter two pictures are interchanged.) There are pictures of modern artifacts like the space shuttle. And there are classical representations of some of the zodiacal constellations. It seems apparent that relatively little production time was devoted to the illustrations used within the book.

However, the editing was excellent. I found no grammatical or typographical errors, and only one possible factual goof. On page 133, white dwarf stars are described as being unable to emit light. I'll give her the benefit of the doubt on this one; she surely understands the difference between white dwarf stars and black holes, and proves it on the next page with a sidebar that describes white dwarfs correctly. And I was puzzled by the reference on page 155 to Angkor Wat being a Hindu temple — said temple being in Cambodia, far from India. But a little Googling4 showed that she is right. The only faults I noticed are that one or two of the descriptions were clumsily worded. This is a credit to the editorial staff at Avon and to Dr. Terenzi's linguistic ability, considering that she grew up speaking a language other than English5 — in what relative measure it is impossible to guess.

In summary, I judge this book to be worth reading, perhaps worth buying, but definitely not worthy of a place in my personal library. By itself, it does not greatly advance Dr. Terenzi's mission of reforming the practice of science. And yet it may, in an indirect way: By serving as a vehicle to "sell" Fiorella herself. In that respect, it does a superb job. She comes across in its pages as intelligent, articulate, capable and persistent, highly creative and talented. Her narrative also reveals her to be very lively and passionate. I'll wager that, after reading her book, you will want to meet this woman.6

In fact, I consider it likely that any man would feel that way immediately upon seeing the cover of the book. You'll remember I said above that not much effort went into the illustrations used within the book. I chose that wording purposefully to exclude the cover art — because the cover art is, IMHO, a masterpiece of sales technique that evinces great skill and craftsmanship. An old adage says you can't judge a book by its cover, and that applies even more strongly to the book's author. But I sought to make just such a judgement when I analyzed an image of the front cover before I had read the book. Follow the link below to find out whether I succeeded.

To contact Chris Winter, send email to this address.

To contact Chris Winter, send email to this address.